Cellphone companies keep putting out very nice-looking stuff that’s been shot on cellphones. Sometimes, it’s nice enough to make even quite seasoned eyes look twice, and perhaps question why we’re lugging these hundred-watt, fifty-pound drama cameras around, especially on any shoot that needs to go somewhere rugged and remote.

So, why aren’t we all shooting on cellphones? The pictures are OK, aren’t they?

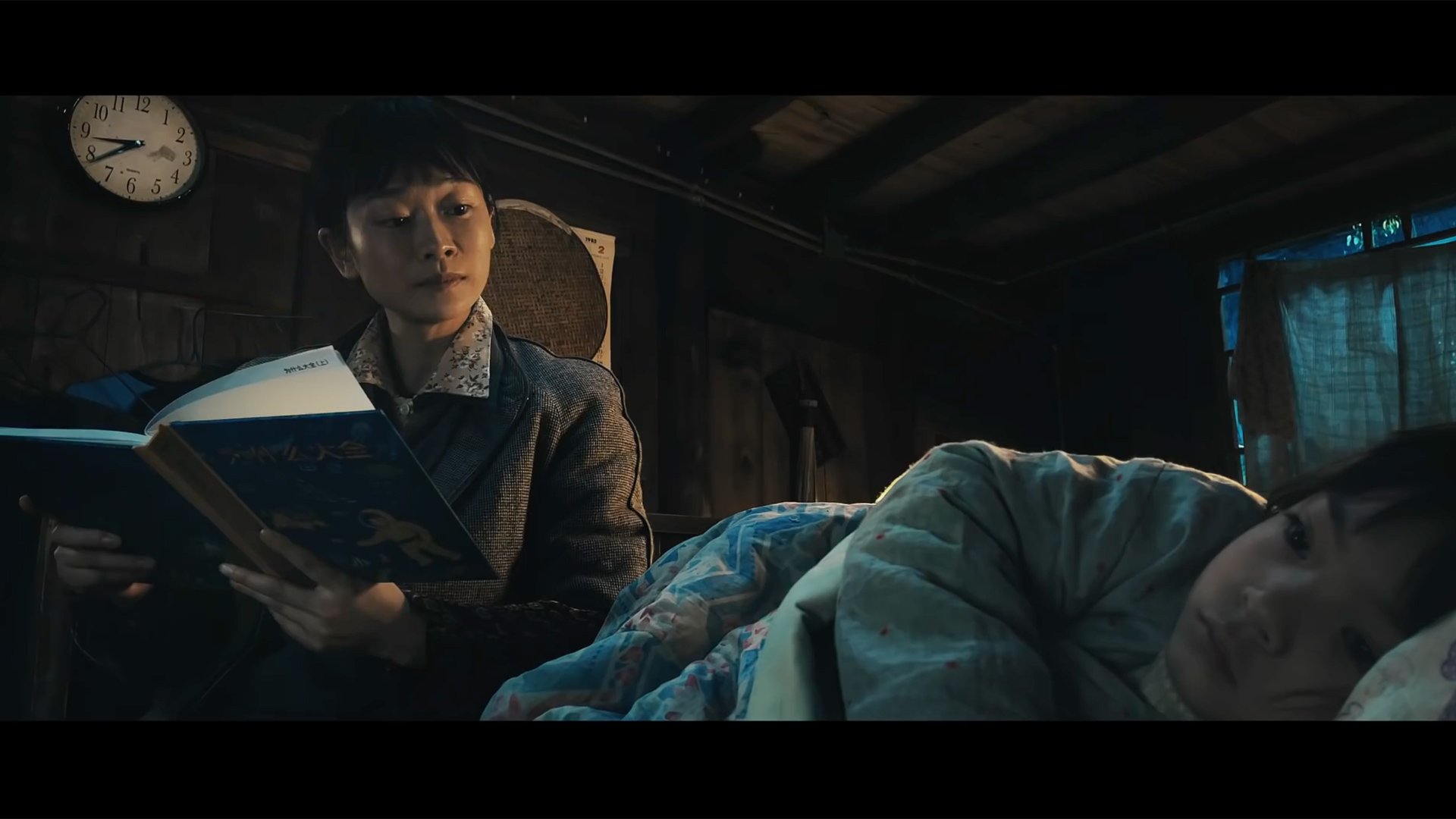

Well, yes. Just based on a subjective analysis of the published images, it’s becoming increasingly hard to complain. That’s been technologically true ever since cellphones exceeded 1440 by 1080 resolution, give or take reasonable noise. After all, someone managed to shoot some sort of sci-fi movie on an F900 once. Cellphones became better cameras than that a while ago. Is the short we linked above compelling; does it look like a movie; is it free of distracting problems? Sure. It’d be quite plausible to put that on a cinema screen or streaming service and expect few if any complaints, regardless of whether it’d make it through a QC with a golden-eyed engineer.

That doesn’t mean we’re blind to the problems. It’s a little over-edge-enhanced. The highlights in people’s eyes are a bit too sharp. It’s heavy on the noise reduction, leaving a slightly plasticky finish to continuous tones. Perhaps most damningly, we see a lot of overcast day exteriors, which are probably the easiest thing in the world to shoot for technical excellence, because there’s lots of light and limited contrast. Highlight rendering isn’t fantastic and where light sources appear in frame they clip harshly. There’s probably rolling shutter, although the operating doesn’t particularly highlight it.

We don’t see what it took to get to this point, and it’d be easy to think that the interiors became a forest of grip and electric gear controlling highlights and specular reflections, although the modern fashion for big, soft sources is friendly to this sort of sensor. Perhaps a bright, sunlit exterior would have shown more problems, but really, we’re reduced to speculating about what might have been wrong in other circumstances. It’s not obviously demanding footage, but it looks, at risk of being ridiculed for having an opinion, pretty legitimate.

So, why aren’t we shooting movies on cellphones?

It’s been done, mainly as a stunt. The problems are mainly practical, and while many of them are solvable, the solutions tend to dilute the usefulness of the phone as a tiny and highly-portable camera system. Let’s assume that we’re running some sort of app that gives us adequate control over the camera in terms of sensitivity, shutter speed and focus, though we’re inevitably relegated to menus full of fiddly controls. Let’s also assume it creates recordings we’re happy with and that we’re using one of the modern, multi-camera phones capable of something other than hyper-wide angle photography.

Practicalities

Assuming we want our movie to look like a movie, we will at some point need to attach the camera to a head of some type. There are gimbals that’ll take phones natively, but often there will be a need to bolt it down to a 1/4” thread. There are clamps for that, with varying degrees of sturdiness and security. The resulting setup might need quite a bit of rigging to be really operable even then, depending on exactly what we want to do with it. Handholding a phone in the conventional style tends, after all, to make things look like – well – a cellphone.

Problem two is viewfinding. While the phone naturally has a big, bold display, it’s not hard to end up in a situation where the operator needs to lie down on the floor in order to monitor the frame if we’re interested in a low angle. It’s an issue that attends many small cameras with fixed, rear-mounted displays, and it often means external monitoring. That’s not even possible on many phones, and even on an iPhone, that means the adaptor module and a monitor; the monitor might also need external power.

To some extent that’s actually quite useful, because that same module will let us feed the phone with power. We need to do that because most phones won’t sit previewing video for hours on end with just internal power; they’re made to last the day in someone’s pocket, not to endure twelve straight hours on a tripod, feeding a monitor. That monitor might need 12V power and the phone needs USB, of course. USB might be part of some modern batteries, although a USB power converter – that supports all the high power charging modes – might be yet another box to strap on to something that doesn’t really have anywhere to strap things on.

Suddenly it’s clear that we’re creating something of a hydra of wiring and electronics on top of that pile of rigging accessories we started with, and we still don’t have proper lens control, nor much selectivity in depth of field even if we did.

It’s possible, then. But like a lot of things that seem instinctively questionable, there are some fairly big problems and the solutions are costly in money and convenience. At the other end of the scale, things like Arri’s most upscale implementations of Alexa include wireless transmitters and lens control receivers specifically to avoid the sort of spaghetti wiring issues we’re describing here.

All of this might easily cost and weigh more than a basic DSLR, which is a far better camera.

Perhaps one day someone will make a tiny movie camera that embraces all of the postprocessing done by phones that allows their cameras to perform so well in such a variety of circumstances. For the time being, though, that sort of technology is best leveraged the sort of camera that rides down a ski slope attached to someone’s head.

Tags: Production Opinion

Comments