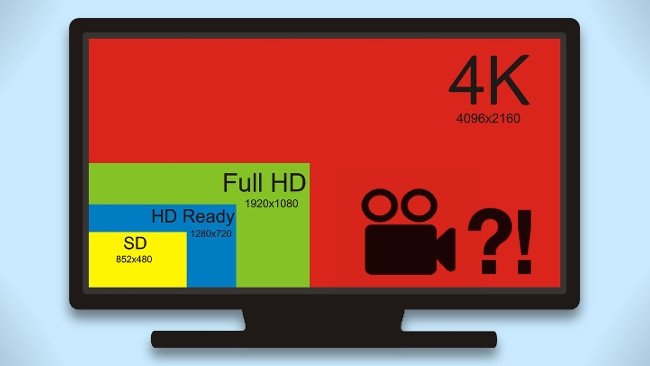

We explore the topic of current 4K viewing from the consumer angle and how it relates to professional solutions.

It's been a while now since 4K cameras became fairly accessible. Simultaneously, the cost of really high-res LCD panels has plummeted, to the point where it's possible, albeit not that common, to end up buying what's referred to as a 4K (really 3840 by 2160) display without really noticing. There's all sorts of conversations to have about how much this has to do with real, definable requirements for increased sharpness in people's home TV experience (and how much it has to do with the commercial need to keep selling new TVs), but that's not the subject of our thesis today.

Let's assume we've equipped ourselves with a shiny new 4K display, which, to forestall argument, we'll use as a blanket term for everything of 3840 by 2160 and beyond. Let's also assume we've found ourselves the proud owner of some sort of 4K camera. If this was all happening at 1080p, finding a convenient, home-user-oriented route from one to the other would be simplicity itself, but that isn't yet quite the case with 4K.

Blu-ray redux

Well, okay, on one hand it is, because several manufacturers – perhaps most prominently Panasonic, with its DMR-UBZ1 – are either currently distributing or to imminently release ultra-HD Blu-ray players. There's an interesting comparison between the current situation and previous advancements in home entertainment technology. Previously, the gap from standard-definition to high-definition content was bridged by a significant increase in bitrate and space on the storage medium. Blu-ray discs, which generally offer 50GB of storage for feature film distribution, are considerably more capacious than 4.7GB DVDs.

Similar things hold with regard to the bump to UHD, although by a rather smaller factor – multi-layer Blu-ray is being proposed for 4K content, providing up to 100GB of storage for a movie. To be fair, that's four times the storage of a common HD Blu-ray title for a picture with about four times the resolution, so it should work fine; the problem is when people start talking about high frame rate and high dynamic range material, which will naturally consume more space. The application of the h.265 codec will help, at some cost to the complexity of the players and the time required to encode the movie.

Watching your 4K

None of this solves our immediate issue of how to watch 4K we've just shot. The tools to produce 4K Blu-rays clearly exist (high-end mastering software company Scenarist talks about it on its site), as there are, just barely, 4K titles to watch, but the standardisation for the format was only announced in May this year and there's clearly been a rush to get material into retail for the holiday season. 4K Blu-ray mastering for the masses, as exists for DVD and HD Blu-ray, is, to stretch a euphemism, some way from maturity. It'll come – it's just software – but not yet.

The most obvious immediate alternative is simply to upload the material to YouTube. Lots of services stream 4K material over the internet, Netflix, Amazon and Vudu chief among them. They're all taking huge advantage of the generality of internet infrastructure and the fact that, again, it's just software; there is no need to produce an enormously expensive broadcast infrastructure of transmitters and receivers to make distribution possible. The pictures are unlikely to be as nice as Blu-ray could achieve, given its clever compression and high bandwidth, but with care it's possible to fit reasonable-looking UHD down a stream that won't bankrupt the internet connections of anyone with an optical fibre within half a mile of home. It's possible that these considerations will provoke an increased interest in encoders that do a really, really good job, which is no bad thing. The huge advantage, of course, is that YouTube is effectively free for both distributor and user.

The only concern is whether the YouTube app on any specific TV actually supports 4K streaming, regardless of the size of the attached display. It's quite possible to find TVs which have fairly elementary onboard computing capabilities (often they run Android) which lack the capacity to download, understand and display a 4K YouTube stream, even if they have 4K displays. Careful enquiries are in order when making a purchase. It may ultimately end up being necessary to patch a computer of some sort (whether that's a particularly capable tablet or a basic PC) up to the TV and simply use it as a display.

Monitoring your 4K

With this (and our audience) in mind, it's worth touching on the world of monitoring. In the world of studio production, it's now relatively straightforward to find SDI and HDMI devices which can handle 4K material, although higher frame rates, 3D, 4:4:4 RGB and other, more advanced trickery may require the 6-gigabit revisions. Ask for all of those at once and you may need the even more rarefied atmosphere of 12-gigabit SDI. The problem with these things, as ever, are that while basic capability tends to emerge quickly, it can take a while to address the lack of problem-solving tools and devices. For instance, Blackmagic hasn't come up with a 4K-capable version of the HDLink device which is so widely used to do basic LUT transformations. Other devices are available, but prices remain oriented to the early adopter and the high-end.

To remain briefly in this studio-oriented world, there are some professionally-oriented 4K devices that could, in extremis, be pressed into service as simple players. An Atomos Ninja Assassin can, in theory, accept externally-rendered ProRes files (or just record external input) for playback and actually costs the same amount as (even a bit less than) the early 4K Blu-ray players. It's worth mentioning that getting these hardware devices to accept externally-rendered files can be a little tricky, requiring some fairly custom approaches to encoding, since the ProRes decoders in hardware devices can be a little pickier than the software codec in something like Quicktime. Still, it can be done. Similar things can be achieved with Blackmagic's Hyperdeck Studio Pro. This isn't necessarily a very sensible solution for day-to-day home use, especially since any 4K signal that appears on an HDMI port is likely to suffer copy-protection restrictions which mean these devices will refuse to record it, but this sort of approach is already being used in, for instance, corporate work to put very high-res video on very big displays.

All of these things will get easier with time. If nothing else, all of this throws into sharp relief the price-to-performance chasm that exists between relatively recent video tape formats and the capability of the internet and IT-oriented broadcast hardware. At £1500, a Hyperdeck Studio Pro or Shogun gigantically outperforms a six-figure HDCAM deck of barely ten years ago. Even if the pace of change is a problem in itself, the brave new world is hard to object to.

Graphic by Shutterstock