As much as a film is intended to be viewed as a whole, inevitably there are performances, scenes, images, special or visual effects and lines that are remembered more than others. This applies to sound design as well and in particular The Piano (1993), one of the early demo selections used to show off 5.1 surround during the 1990s.

As the standout sequence appears in the opening credits and is reprised in slightly different form, towards the end, it risks overshadowing other, subtler examples of what audio can bring to such an otherworldly, evocative story.

The overall impact of the sound design can be reassessed with the forthcoming release of a 25th-anniversary edition DVD of The Piano, which follows a recent short theatrical run at the BFI South Bank in London. The film, set in the 1850s, is largely about repression and although it illustrates the lower-key, atmospheric power of 5.1, it does have obviously dramatic aural moments.

The central character, Ada (played by Holly Hunter), is introduced through a voice-over saying she has not spoken since the age of six. Consequently, the narration is delivered in what is described as the voice of Ada's mind. This is accompanied by the somewhat portentous music of Michael Nyman, who provides a more flowing, orchestral score compared to the strident minimalism he produced for Peter Greenaway's films.

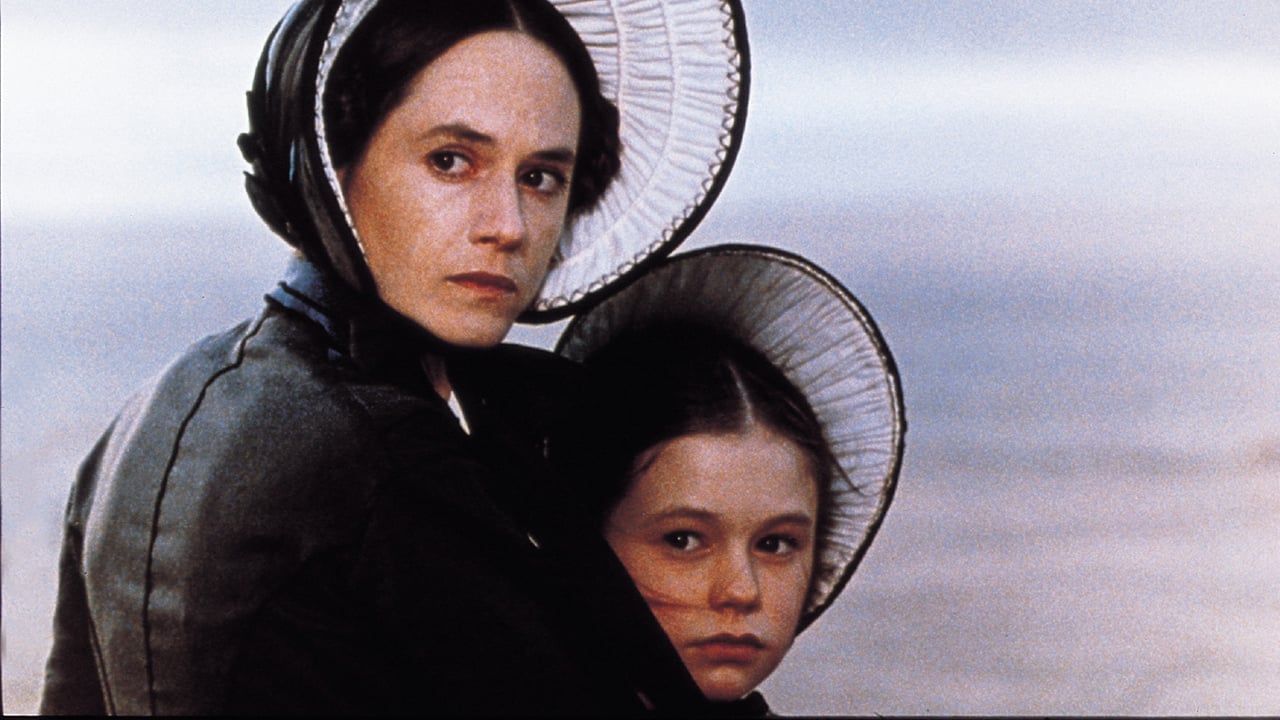

Ada's locked-in personality is contrasted with that of her boisterous daughter Flora (Anna Pacquin), who is first seen roller-skating noisily on a wooden floor in an old, big Scottish house. Their lives change suddenly when Ada's father arranges for her to marry Alisdair Stewart (Sam Neill), who has settled in New Zealand to run a farm. Mother and daughter arrive in the new country after a long sea journey, brought ashore amid the noise of crashing waves, wind and shouting sailors.

Ada and Flora are accompanied by heavy trunks and the musical instrument of the film's title, encased in a wooden crate. As the men struggle to beach the overloaded, long rowing boat, the camera and the sound dip under the water and beneath the vessel. Unsurprisingly this is the sequence that grabbed the attention of audio fans and, in a move that suggests director-writer Jane Campion realised its impact, it is synchronised with the on-screen credit for sound designer Lee Smith as part of the opening titles.

All encompassing

The effect is all-encompassing, giving a sensation of movement, plus the feeling of panic and claustrophobia one experiences when falling into the water. The boxed piano is unloaded with much creaking and groaning of the wood. The instrument is Ada's primary form of expression and she becomes agitated during the process of bringing it to land. Once it is ashore she sees a crack in the crate and is able to reach the keyboard, playing it to produce an echoey, enclosed sound.

Because of its bulk, Stewart refuses to transport the piano to his house immediately, ordering it be left on the beach, much to Ada's distress. The new arrivals are taken away, squelching through the undergrowth as rain and thunder close in. These natural sounds reoccur through the film, playing the oft-used, traditional role of sympathetic background to the emotions on screen. Inside Ada's new home the laughter and chatter of the servants, punctuated by tapping and other noises off, imply that business is going on elsewhere, which takes Stewart away from his bride-to-be.

The piano remains on the beach amid the pouring rain, accompanied by one of Nyman's more stirring themes. Through Flora, Ada persuades another settler, Baines (Harvey Keitel), to arrange for the piano to be moved. Baines refuses at first, but the women keeping coming to his cabin, wearing him down. The scenes of Flora going to see Baines are accompanied by a flute motif that becomes more discordant as she chips away at him. Finally, Baines gives in, on the understanding that Ada teaches him to play.

The lessons are underpinned by an erotic, sexual tension, although, at first, not much happens. The piano's influence extends beyond giving Ada a voice to conveying what Baines feels and doesn't say. Eventually, the two consummate their passion, forcing Stewart to board his wife up in her rooms. Ada later gives Flora a message for Baines written on a piano key, which the child takes through the forest while rain pours down and thunder rumbles in the distance, creating a sense of foreboding.

On learning of this, Stewart chops off one of Ada's fingers in a very underplayed scene, although the blow is still quite sickening. Stewart finally agrees to Ada and Flora going away with Baines; the three travelling away in a Maori canoe with the piano strapped on its middle. As they pull away from shore, Ada gestures to dump the instrument over the side. As it sinks, the water produces booms and other strange noises against the strings and sounding box. A rope attached to the piano uncoils and Ada deliberately catches her foot into it.

In a re-run of the earlier underwater sequence, she is pulled overboard but instead of panicking appears to serenely accept her impending death. Air bubbles bloop around her as the thing that was her life for so long drags her towards a watery grave. Suddenly, Ada changes her mind, struggles free and makes for the surface, gasping for air as she breaks the surface.

Ada's girl voice tells us that although she saw death as a chance to escape, she decided to start again, learning to speak and settling down with Flora and Baines. She does not abandon playing, although it is different as her new metal finger clicks on the keys. Her old piano now sits on the ocean floor but not in silence; it still produces some strange, indistinct sounds, showing how that part of Ada will never die.

Tags: Studio & Broadcast

Comments