RedShark Technical Editor Phil Rhodes lifts the veil on Dolby Vision, a revolutionary high dynamic range display system that could change how films are made and shown.

It's difficult to refer to something caused by technical excellence as stagnation, but there's no way to avoid the reality that a few technical disciplines have been – let's say – searching for reasons to advance. Perhaps the clearest example of this is in digital audio, where precision and dynamic range has been more than enough to fool human hearing for some time. There are ancillary advancements to be made and new features to put into new equipment, but it's still arguable that we're beginning, to some extent, to reach the same point with pictures.

It's been a while coming, given the gigantically larger data rate of the moving image over audio, although the considerations are the same: there are valid concerns over the usefulness of 4K outside theatrical exhibition. Even when improvements are unequivocally directed at greater realism, we find that higher frame rates are not what audiences seem to prefer, and 3D has been (at best) a partial success. Dolby, though, has created something genuinely new in its Dolby Vision technology, which is designed to improve an aspect of imaging that has been perhaps rather overlooked.

Improved dynamic range through addressable backlighting

Local backlight dimming, where a TFT panel is backlit by a matrix of white LEDs which are individually controllable, is not a new idea, but so far it's been used mainly to create monitors that more closely match existing standards, as opposed to deliberately exceeding them in order to create something visibly better. The first tests were done some time ago by projecting the picture from a digital cinema projector onto a surface the size of a traditional monitor, with surveys indicating a strong preference for brighter and more contrasty pictures.

The poor static contrast ratio of a traditional TFT display, with brightness around 300 nits (where the nit is a unit of brightness equivalent to one candela per square metre) isn't difficult to exceed in experimental circumstances. However, making a high dynamic range display that can be manufactured and sold, and a system to standardise the signals sent to it, is more taxing.

14-bit or 12-bit production

The challenges of making any significant change to the way moving pictures look are split effectively into two: how we shoot the pictures and post-produce them, and how we ensure they're properly displayed. Because Dolby Vision is a significant departure from what has gone before – more different from the norm, for instance, than Rec. 709 is different from Rec. 601 – some bolder approaches to standardisation are required.

In production, it's clear that much more precision would be required in order to effectively represent such a wide range of brightness – up to 14 bits per channel, according to the company. This can be mitigated in more or less the same way that we use logarithmic (or log-like) encoding to store camera original material that Rec. 709 can't handle very well, using a specially-designed gamma encoding. Dolby has designed gamma curves that allow Dolby Vision material to be encoded in 12 bits, making the data a little more lightweight.

Superior images (even on lesser displays)

Regarding presentation, Dolby is currently demonstrating two displays, one of which is now being shown in public and has a brightness of about 2000 nits (something like seven times that of an average display) and another, higher-end grading reference monitor at a genuinely dazzling 4000 nits, which has been viewable behind closed doors for a while.

While both of the demonstrated displays are laboratory experiments and not intended to become products, the company has also recognised that real-world displays are likely to offer similarly variable capability. As such, they have developed an interesting approach to distribution where material is graded on a high-dynamic-range reference display, and then trimmed in a second grading pass for the best possible appearance on a Rec. 709 display (by applying, presumably, a dynamic range compression that ought to be reasonably consistent and straightforward). The intent is that the full dynamic range material would be distributed alongside metadata describing the trims necessary to create the Rec. 709 result. A particular monitor would then apply those trims to the supplied high-dynamic-range images to a varying degree depending on the display's capability, creating the best possible result for a given implementation of the technology.

Check out Page Two for the continuation ot this article and to view a video profiling Dolby Vision!

Standing in front of a Dolby Vision display

That's the technical approach, and it makes sense. What makes this spectacular, though, is the actual appearance of the displays, which is difficult to demonstrate since I don't have a camera of sufficient dynamic range to photograph them and, until Dolby licensees start selling Vision-enabled computer monitors, you don't have a display capable of reproducing such an image. The only approach is for me to subjectively describe the results as, to put it mildly, very highly compelling.

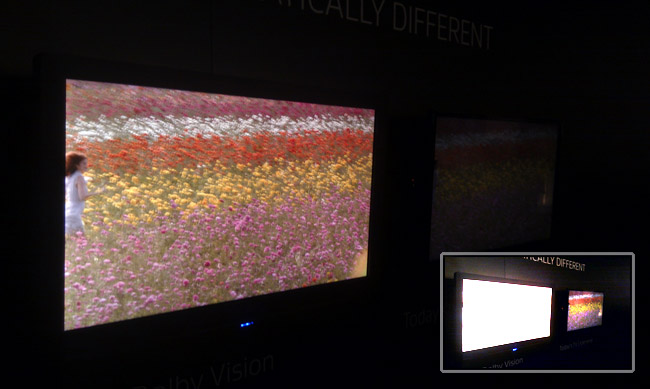

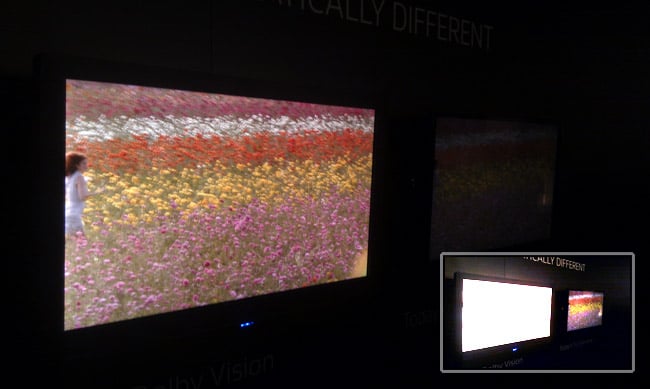

Main: Exposed for Dolby Vision in foreground. Inset: Exposed for conventional monitor in background. Note the large difference in display brightness that exceeded the camera's dynamic range.

Main: Exposed for Dolby Vision in foreground. Inset: Exposed for conventional monitor in background. Note the large difference in display brightness that exceeded the camera's dynamic range.

The difference between the 4000-nit reference display and a good Rec. 709 display is actually not as spectacular as the difference between the 2000-nit display and an equivalent TFT-based domestic television. This is frankly because the domestic television is nothing special to begin with, but in both cases, the improvement with Dolby's new technology is profound. The TFT panel used in the 2000-nit display and the domestic TV is identical but the difference between the images could not be more marked. Domestic displays are a soft target, since many current TVs suffer backlight bleed, viewing angle problems, and other issues which make it, on average, a mediocre technology.

Displays using local dimming LED backlights have been made before and the improvement is enormous, despite the fact that this must be an approximate technique which provides excellent (theoretically infinite) global contrast, but no better local contrast than the TFT panel alone could provide. There are also concerns around power supply and cooling, which mean that the entire panel cannot be driven to peak white simultaneously, although one would hope that this can be mitigated by good engineering in professional models, where variable absolute brightness with different picture content would be hard to live with. Subjectively, though, the technique has always been successful (witness the success of Dolby's PRM-4200 reference display) and Dolby Vision is a particularly spectacular expression of it.

The experimental displays on show aren't without problems. The extremely high peak brightness of the 4000-nit display creates a certain amount of blooming, which looks to be caused by light bouncing within the very front-most layer of the display, and at this stage one can only guess at the price licensees will have to charge. But if we're tired of 3D, and if 4K just doesn't offer all that much real improvement, and if we're looking for the next significant advancement that should really make pictures look unquestionably better in the eyes of more-or-less everyone, I would be very pleased to find that Dolby Vision is it.

Tags: Studio & Broadcast

Comments