Sharp eyes may have noticed Sony’s announcement of a very large, very high-resolution imaging sensor, the IMX661. Why do we care? 127 megapixels, that’s why.

Sony’s new design, part of its Pregius range, is even higher in resolution than the sensor in Fujifilm’s mighty GFX 100 medium format camera while being broadly the same size – and it offers global shutter. So, if we really need a 13.4K, significantly-beyond-VistaVision camera, it’s clear Sony now has the capability of building one – though actually it’s not necessarily, mainly, a video sensor, for reasons we’ll get to in a minute.

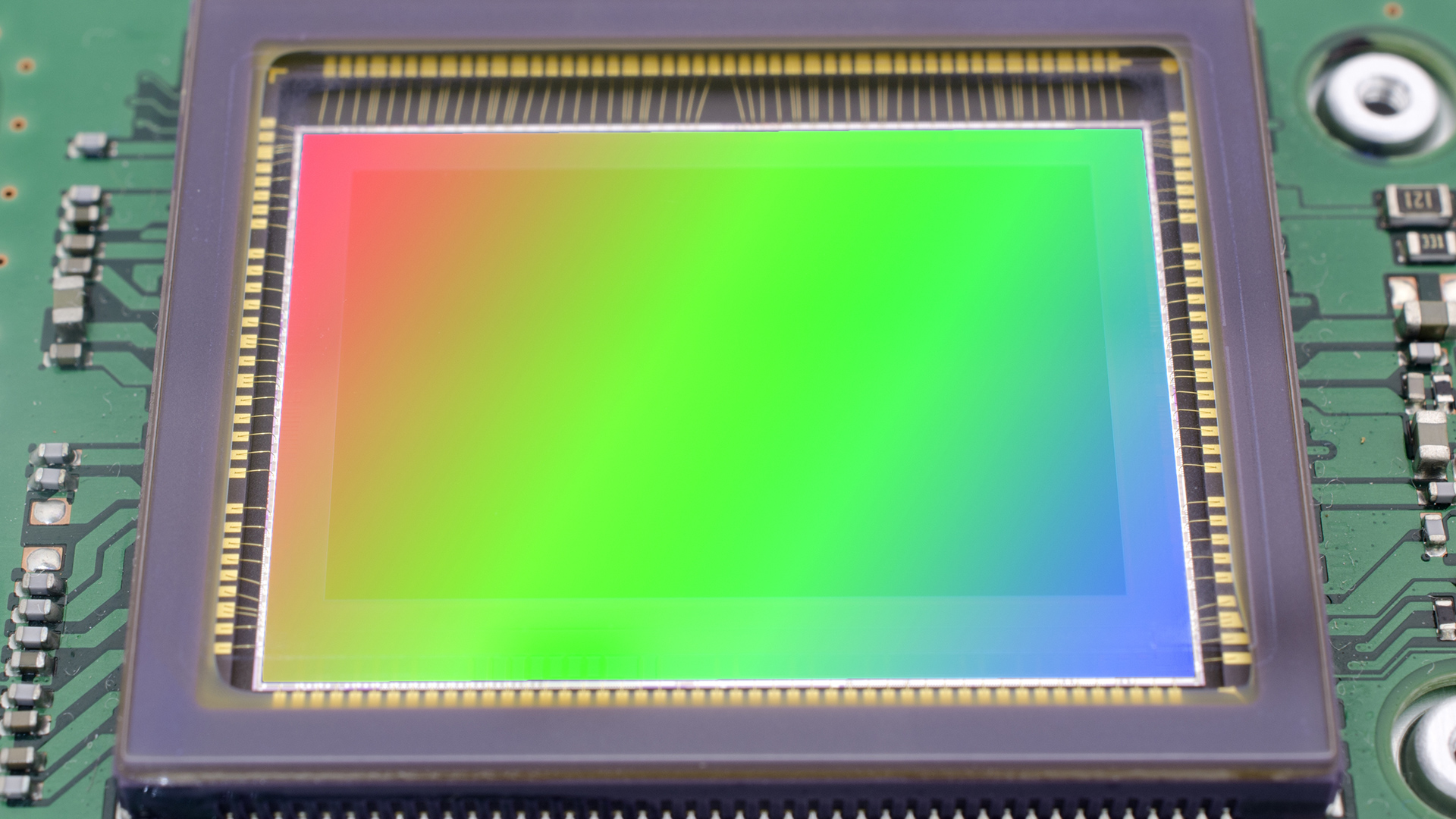

Certainly it’s clever. Making this sort of chip happen requires all kinds of advanced techniques, with silicon stacked on top of silicon to get the analogue-to-digital conversion circuitry into a convenient position. All imaging sensors are, at their core, analogue devices, with each photosite holding a charge level that’s affected by the light that falls on it. That’s not generally something camera designers have to deal with directly since all modern sensors offload their data digitally. That means transporting the tiny signals from the individual photosites to the analogue to digital, a task beset by huge challenges around inductance and capacitance, which risk smearing signals to the point of unintelligibility if not handled carefully.

IMX 661, what's it for?

Sony has a long history of doing this sort of work, so what’s perhaps most interesting is exactly what goals the lab-coated people were working toward when they designed the IMX661. The information released talks mainly about what sounds like machine-vision applications. Particularly, the reported existence of a monochrome version suggests that applications such as automated inspection systems in manufacturing. Whether or not anyone will ever feel the need to use that monochrome sensor to build a truly epic triple-flash RGB film scanner remains to be seen.

It’s hard to overlook, though, that this is a medium format sensor, and Sony might be interested in an answer to the Fujifilm GFX 100. The usefulness of that naturally relies on a lot more than just resolution, though. It’s particularly difficult to assess the real-world noise performance, since Sony doesn’t even use the word “noise” in its released information. With photosites necessarily a little smaller than the GFX 100 (3.45 versus 3.76 micrometres), we might hope for greatness, although global shutter does traditionally cost us something. In fact, it often costs us quite a lot, to the point where the sensor in the Blackmagic Ursa Mini 4.6K is theoretically capable of it, but it isn’t implemented in the camera’s firmware because the penalty in noise, sensitivity and dynamic range were judged to be a compromise too far. The fact that this sensor offers up to 14-bit output doesn’t tell us how many of those bits are noise.

Not a video sensor?

The other thing that probably does stop it being a video sensor – at least in its full, 14-bit, 127-megapixel glory – is that the maximum frame rate is 21.8 frames per second. This is apparently a limitation of the digital links used to move data off the chip, and since it has region-of-interest support, it’s presumably possible to increase that frame rate by reading out less of the chip. Using some possibly rather naive calculations, the VistaVision-sized area might give us a frame around 10.5K wide by 5.3K high, for a total of about 56 megapixels. That’s more than twice the effective width of an Alexa LF and 75% more than a Venice. To be fair, the photosites on the Sony chip are under half the size and possibly hampered by the global shutter, but improvements in the field might well make up a chunk of that difference, and downsampling more than 2:1 to a 4K result should help even more.

It’s a large leap to assume that windowing to VistaVision on Sony’s new chip would allow us to double the frame rate, but assuming that’s true it might then be possible to push 50fps on a 10.5K native, unscaled VistaVision sensor. That would be a competitive capability, though this is all idle speculation, and it’s much more likely that this is a chip destined for a GFX100-style stills camera that would struggle to record a 10K-plus image. It’s probably truer than ever, though, that resolution is a won war. The GFX 100, for the sake of comparison, gives us 4K at 30fps based on an on-sensor downsample of the full sensor width.

All of this is idle speculation until Sony announces a camera, of course, but it hints at intent and potential capability.

Tags: Technology News

Comments