Bait is a modern film shot on a clockwork Bolex camera. A case of artistic license going a little too far?

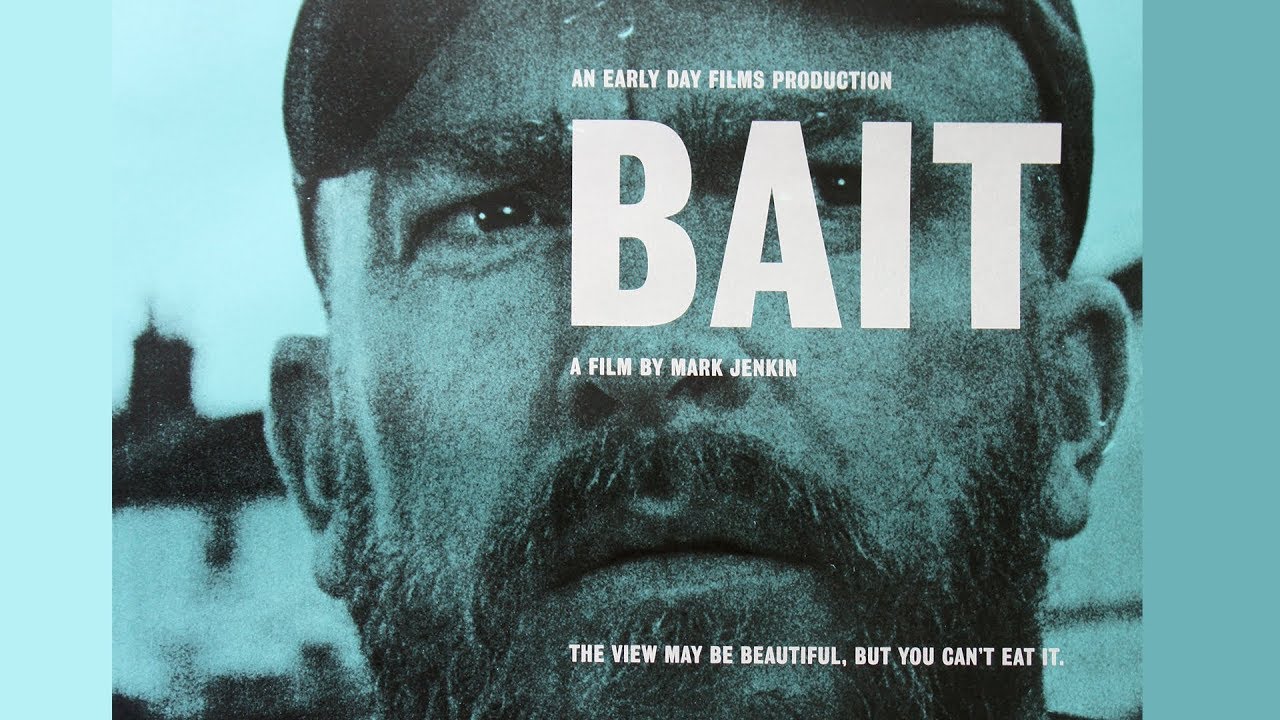

When a message from the British Film Institute dropped into my mailbox with the heading ‘The definitive British film of the decade', I thought I’d better investigate. The film, it turns out, is one that has been discussed on RedShark before, but I thought it was worth pursuing further as it connects to various issues that come up frequently. I’ve now watched it all the way through. The film is Mark Jenkin’s Bait and is remarkable for a number of reasons: it’s a feature drama shot with a clockwork Bolex H16 on hand-processed black and white 16mm, entirely post-synced. Mark Kermode, the critic who called it the definitive British film of the decade, also called it a ‘genuine modern masterpiece’. It has a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. It reminded me of as nothing so much as the output of the 16mm filmmaking courses I ran many years ago – in fact, in part, it’s a textbook case of many things we were trying to avoid.

If you’ve never shot with a clockwork Bolex, there are a few things you should be aware of. Because of the windup spring motor, shot length is limited to around 20 seconds. You can’t shoot sync sound, not only because the motor won’t run to accurate speed, but because it makes a hell of a clattering sound.

Small gate

The 16mm gate is, by modern standards, very small. Hence, you are working with short focal length lenses for the same angle of view (25mm is a ‘standard’ lens in this format) so you are never going to get the shallow depth-of-field look so popular today. Which is probably a positive thing, given that the viewfinder is very dim, so it is very hard to focus (it’s a prism rather than mirror reflex which ‘steals’ part of the image before it gets to the film). It’s almost impossible to follow focus when shooting on the tiny C-mount lenses, so it is notable in Bait that, when shot on longer lenses, characters walk into their focus point and then out of it again. And, unlike more sophisticated 16mm cameras, there’s no magazine to take off to check and clean the gate. If you get a hair-in-the-gate while shooting, it stays there. Shooting on an antique Bolex is not easy, so making an acclaimed drama on one is certainly an achievement.

In conventional terms, Bait’s hand-processed stock looks awful. Camera hairs, scratches and a filthy negative means there is a continual parade of white blemishes and hairs on the print. The density of the negative continually changes. At times, the image is constantly flickering and the picture flashes into negative. The quality is very inconsistent; a sharp, contrasty shot is followed by a foggy one that looks like it’s been dragged through the dirt. You understand why professional filmmakers always let professional labs develop their film.

Authenticity

To some it might give a sense of authenticity but, if you grew up shooting films on a clockwork Bolex, it seems the opposite. The ropey image looks mannered and a little pretentious. Although promoted as a low-budget movie, shooting on film, even on a clockwork Bolex, is never the cheapest way to work. So, the question is: Why? And did it work?

It really comes down to style - there is a very distinct feel to the whole film. It looks like no other movie made in recent years. If you ignore the flickering and the blemishes, there is, at times, a beauty to the sparkling and occasionally stunning monochrome image and, whatever it looks like, you know this ain’t video.

Despite the extreme style, the story and structure of the film are surprisingly conventional. A gritty tale of a Cornish fishing village and the conflict between the obnoxiously arrogant middle-class city incomers and the struggle of the local fishermen to make a decent living. A fisherman’s cottage becomes an AirBnB where the working tools of the trade – nets, floats and lobster baskets – become picturesque wall decoration and tourists complain about being woken too early by the fishermen’s boats. It’s a strong story with much relevance to any community where tourism is the replacement for dying industries and traditional ways of life become a spectacle for the urban wealthy.

The acting is generally rather good but, because all of the dialogue is post-synced, performances take on a strange awkwardness. This distancing effect is part of the particular style of the film, but it removes the chance for any nuance in the performances. We do, however, get a lot of moody, big close-ups and some bold cross-cutting that has an almost Eisensteinian feel.

The modern alternative

If it had all been shot on digital video, would it have been a better or worse movie? Certainly shot this way it makes it appear a bit special. The ‘hand-made’ feel gives you the sense that every shot has been painstakingly chosen. Shot more conventionally, the film would certainly have gathered less attention and it certainly wouldn’t have been acclaimed as ‘the definitive British film of the decade’.

On the other hand, shooting digitally would have allowed the filmmakers to go for many more takes and add subtlety to the performances which is severely lacking. To be honest, the style covers up many of the weaknesses of the movie — the very basic lighting, the stereotyped characters and a certain lack of resolution to the story. Having said all that, I actually rather like this film and I can’t help admire the audacity of the filmmakers who have taken a particular approach and pursued it till the end. And, given the overall critical success, you could say it worked.

What is interesting about Bait is that it takes issues we have often discussed here, like admiring lenses with ‘character’, getting away from ‘clinical accuracy’ of the digital image and the gritty appeal of film and pushed them to the limits. Or possibly, beyond the limits.

So is this film a bold and successful attempt to go back to basics and achieve a sense of authenticity, or is it an example of the triumph of style over substance? Is the rough, hand-processed look a key feature or a distraction? Let me know what you think.

Bait currently has a limited cinema release and is available on BFI Player.