Replay: The two Star Trek series Deep Space Nine and Voyager are still not available in HD. Both were shot on film and could be beautifully remastered in exactly the same way as the first two series produced under the Star Trek banner. It hasn’t happened and it doesn’t look like there’s any realistic chance of it happening. Why?

The noble art of kaboomei. In theory, remastering this is as simple as entering 1920x1080 in a box and hitting render. In practice... well... Here's hoping those pyro elements are HD

Most people are quite keen on the idea of getting paid twice for doing the same work and people involved in the production of film and television are no exception. They’ve enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship with home AV equipment manufacturers over the past few decades, ensuring that films made 40 years ago are repeatedly resold, motivating the sale new equipment. It’s easy to scowl at this as a commercially motivated process, but it’s also given us DVD, high-definition pictures and HDR, the development of which had to be paid for somehow.

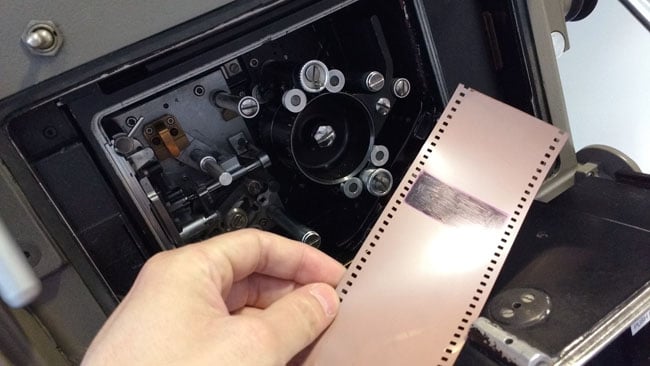

Film makes things easy, especially if it's this vast

It's also given us eye-bending post-converted stereo 3D (“postcards in space” as one sour-faced misanthrope put it) and high frame rate (“soap opera mode” said the same person), so progress hasn’t been without the odd cul-de-sac. Usually, though, the parallel development of technology to bring better pictures to everyone’s lounge has been easy to like. It’s also made film purists feel rather smug because its 35mm negative has enough information to remaster productions originally finished in 480-line NTSC in 4K HDR.

Where that leaves productions shot since the mid-2000s, on a variety of electronic formats with a variety of capabilities, is anyone’s guess, especially given the fact that some cameras now produce files which are not publicly documented, possibly deliberately obfuscated and not nearly as intrinsically comprehensible as a plastic strip with some pictures on it.

Film is made using rendered-down dead cow, and it can go off

The issue of archiving is a whole article in itself but even a quick skim of the subject raises issues such as the longevity of media and the readability of file formats. Even film doesn’t last that well without special measures having been taken. Perhaps worst of all, while the archive is now valued as a route to future revenue, there’s often no money left at the very end of production to pack things neatly away.

But that’s a separate issue to remastering. Since we stopped treating TV productions like feature films, to be negative cut, it’s not just a case of scanning a finished show at high resolution. Since the mid-80s, very little television has been finished on film and, in 2019 practically nothing is ever finished on film. So, assembling (say) an episode of Deep Space Nine in HD would require going back to the original negative.

That probably exists somewhere. That wasn’t always the case; the BBC notoriously destroyed a lot of its tape archive, but by the 1990s it had become clear that it was probably a good idea to throw everything in the cellar for later. “Everything” might or might not include things such as the edit decision list or other timeline description for the episode and even if it did, reading a mid-80s nonlinear editor project on a modern system might require a competent software engineer.

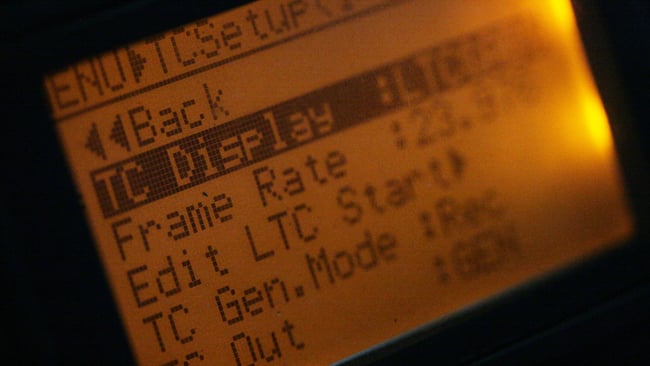

Time code and keycode are comparatively simple things to keep around. Data for full CG scenes is not

The only alternative is to match cut to the episode as it exists. And of course, Star Trek is science fiction, so a proportion of each episode will involve spaceships and rayguns. The actual proportion of that sort of thing in a lot of television, at least up to the money-no-object era of Netflix and Amazon trying to beat each other to death with clubs made of money, was generally pretty small. Series such as Battlestar Galactica attracted snickers for their endless reuse of visual effects shots. That means there might be a film negative to scan, but visual effects material is often less well archived than live-action photography. By the end of The Next Generation, though, CG had become an attractive alternative, which creates two problems. They were rendered for standard-def TV and there’s never been a standard way to archive that sort of data.

Anyone who’s ever tried to open a Blender project downloaded from the internet and hit endless issues of finding models and textures will understand what might be involved here. This sort of thing has been done. The Lightwave projects representing some of the animation for the original Worms video game intros were recently found on an ancient Amiga 4000 once owned by the games company Team 17 and re-rendered at high resolution on modern gear. Apparently, Lightwave has retained shockingly good backwards-compatibility (and Lightwave was heavily used by Foundation Imaging, pioneers of CG for TV). Still, the Worms scenes are very elementary compared to some of the hundred-ship battle shots done for Deep Space Nine.

With any luck, we'll be able to find the original audio that was recorded on set. Probably the orchestral tracks, too. Anything else...

We should also mention audio since a modern audience keen enough to keep re-buying material is likely to want a nice multi-point surround mix. Again, let’s hope that all of the elements used to create the original mix, from every orchestral music cue to every spot effect, has been archived somewhere.

What we’re talking about here is essentially a repeat of the entire post production process, from the end of the edit through grading and VFX, to the end of the final sound mix. Rumours abound that it cost 12 million US dollars to do this for 170-plus episodes of The Next Generation and that’s a show that’s old enough to have used quite a lot of film originated VFX. Costs for Deep Space Nine and Voyager freed up by the cost savings of CGI, might be higher.

Essentially recapitulating a good two-thirds of the post process for a major TV show is a non-trivial endeavour

If hugely successful and popular series such as these aren’t financially viable remastering projects, then many other things won’t be either. Digitally originated stuff may be easier if only because we understand the need to keep all the material around for remasters. Still, we might have to write off the late twentieth century as a hole in television history, a circumstance under which the Betacam SP masters, containing a pale shade of the film-originated photography, are the best we’re ever likely to get.

Tags: Production

Comments