Replay: These cameras were way ahead of their time, but have been consigned to history. Phil Rhodes continues his examination of cameras that really should have been much more successful, but that had their light extinguished almost before they were a blink in the eye of a photon.

Read part one of this article here.

The Marconi Mk. X, one of only three that were ever made - Picture used with kind permission of Golden Age TV LLP

Marconi Mk. X studio camera (1985)

Marconi had been a major manufacturer of broadcasting equipment almost for as long as radio had been a public service in the UK. For a while it was the manufacturer, and built a successful business producing both radio and television production and transmission equipment through most of the twentieth century. In the 1980s, though, tube cameras were beginning to give way to CCDs, which were smaller, lighter, cheaper, required less maintenance, consumed less power, lasted longer, and would soon eclipse the picture quality of the older technology.

It was a bridge Marconi pretty visibly elected not to cross, and the company never produced a CCD camera. The Mark X was shown in 1985, although it was really little more than a rebadging of another manufacturer's product (sources differ whether it was Ikegami or JVC) and the model was never produced in quantity. This would not necessarily be a particularly notable failed product beyond the fact that the situation coincided with the prime developer of broadcast itself ceasing to be a big name in broadcast.

It isn't fair to blame the end of the tube era or the Mark X camera in particular for that. It happened at least partly due to a spectacularly misjudged switch from broadcast to defence manufacturing which almost coincided with the end of the cold war, and during a period of consolidation in the UK and European defence industries. Had broadcast not been abandoned, and had the economic climate of the UK in the 1980s been different, Marconi might still be a presence at NAB on the same sort of level as Ikegami and JVC. Fragments of the Marconi organisation still exist as part of Ericsson and as Telent, but (arguably) the last company to derive directly from Guglielmo Marconi's original was consumed by defence monolith BAE Systems in 1999.

The Dalsa Origin - Way ahead of its time.

Dalsa Origin (2003)

If cinematography equipment was judged solely on its technical capability, the Dalsa Origin would have swept the market clear overnight. Launched at NAB 2003, it was based around Dalsa's own 3.5K sensor and was therefore a huge advance on any preexisting system; nothing comparable would exist for years thereafter. In 2008, though, having released a followup camera and established a smart rental facility in Woodland Hills, Dalsa got out of digital cinema.

It's easy to point at the size of the first Origin camera as one reason it might have struggled to be taken seriously, though it has been claimed that it was no larger than a 35mm camera with a 400' magazine. It was occasionally shown in a handheld configuration, perhaps in a desperate bid to make it clear that this was at least possible, if not very practical. The revised Origin 2 was much more compact and there was no obvious reason it could not have become a mainstream success. The Origin series was certainly used on major feature films, including effects work for Quantum of Solace and large amounts of the 2010 Tim Burton project Alice in Wonderland, VFX-heavy situations where the huge amount of data is particularly helpful.

But of course cinematography equipment is not judged solely on its technical capability, and the storm of pixels is possibly part of the problem. Storing 16-bit 3.5K raw material uncompressed is comparatively hard work in 2019; it 2003 it required a stack of hard disks the size of a dishwasher. At around the same time, the excellent Thomson Viper camera was encountering similar problems, and Thomson did not follow the Viper up either.

Dalsa, now Teledyne Dalsa, continue in business as a manufacturer of specialist image sensors for applications as esoteric as the Spirit and Opportunity rovers that did so well exploring the surface of Mars, but they have never again dipped a toe into the shark-infested waters of moviemaking.

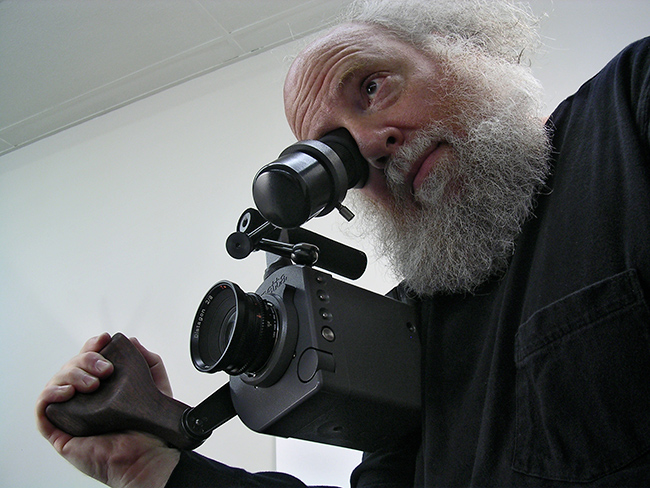

Kinetta inventor Jeff Kreines with his camera

Kinetta (2004)

In 2004, at the NAB digital cinema summit, the Kinetta company showed what appeared to be at least a good mockup of a camera system, if not an actual camera lacking its final firmware. It's not clear quite how complete it was, but fourteen years later Kinetta is the manufacturer of a very respectable and widely-admired archival film scanner, not a camera. Even so, there's still a PDF file on kinetta.com giving specifications of a camera that would have made digital cinematographers of the time eat their Promist filters in a fit of desire if it had ever seen the marketplace.

It was probably the first camera to even promote an OLED viewfinder, and was intended to use onboard magazines recording nearly two hours of uncompressed 10-bit 1080p24. That would have been expensive in the mid-2000s, but would have been a very welcome development. It was intended that a fibre-optic link cable would connect a breakout box with all the conventional connectors, meaning that the camera itself could be small and easy to handle.

Perhaps the most visible aspect of the design was that the Kinetta camera was designed to be a small, handy thing like the 16mm documentary cameras of the mid-to-late twentieth century. It was definitely a digital camera for film people, rather than a video camera bent to single-camera production work. Technologically, it was a raw-recording design that predated Red or even the Silicon Imaging SI-2K in that it offloaded much of the tricky processing work to postproduction. It was a tidy, innovative and forward-looking design, but the only references to “Kinetta camera” on Google now refer to that PDF file and a few news articles and forum posts from the mid-2000s.

The Aaton Penelope Delta

Aaton Penelope Delta (2010)

Aaton's camera arm made several approaches to digital technology in the late 2000s. Probably the first thing to be referred to as “Delta” was the digital magazine for the Penelope film camera that was shown at NAB 2010, though by 2012 the proposed new device, still called Delta, was a complete digital camera system. Both cameras used a 3.5K Dalsa sensor, though both made for a much more compact system than Dalsa's own Origin camera.

The idea of a digital magazine for film cameras was not a new one. It's an indication of just how important familiarity and ergonomics can be that the idea had been discussed particularly with respect to 16mm cameras used for documentary, where the convenience of digital acquisition would be most useful. It's a concept of particular relevance to Aaton, who had long been well-regarded for their dedication to convenient and easy handling.

There are two problems with the idea of a digital magazine for a film camera. First, it's difficult from an engineering perspective, since the space inside a camera body where the film meets the gate is often very space-restricted, and it's difficult to ensure the sensor fits at all, let alone fits in exactly the right place to avoid back-focus issues. The main problem, though, is whether there's any point.

If we're not using the film-advancing mechanism of a film camera, it really becomes nothing more than a convenient way to hold a lens in front of a sensor. It has a rotating mirror shutter and a viewfinder, but otherwise, a film camera that isn't being used to handle film is really just a glorified lens mount, and it might not make sense to do complex engineering on a digital magazine just to make it work in an existing camera body.

Either way, by mid-2013, Aaton had declared bankruptcy, and was bought out by Transvideo. It survives as a manufacturer of the extremely high quality Cantar series of audio recorders.

Tags: Production

Comments