Replay: Roland Denning looks back on the Mitchell BNC, a 1940s camera which has influenced filmmaking right up to the present day.

This is the second of my very partisan, unscientific appraisal of cameras that have changed the way we make films, decade by decade. This is not a precise historical survey. Basically, it is an excuse to talk about the ever-fascinating subject of movie cameras, their evolution and how we interact with them.

In the first part, covering the 1930s, I chose the Bolex H16 – a clockwork 16mm camera first produced in 1933 that is still (just about) available today. For the 1940s I am looking at the other end of the spectrum – the motion picture studio camera.

The Mitchell BNC

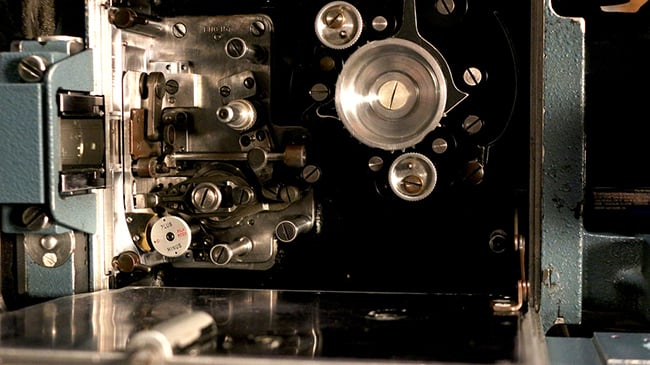

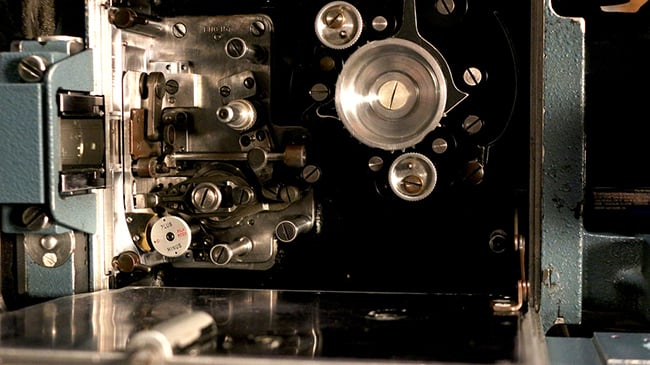

The 1940s can be reasonably considered as the golden age of Hollywood – or perhaps the first golden age. Talkies had been established for more than a decade, the studio system was at its height and the language of cinema itself had evolved to its most sophisticated form. If you picture the classic studio camera of this era, it is probably the Mitchell BNC, as seen in this short clip.

I have cheated here a little as the first Mitchell BNC cameras appeared in the 1930s, but because of World War II, there was only one camera made between 1939 and 1946. The forties was the decade the Mitchell owned. In 1941, the Mitchell BNC Serial No2 was rented to RKO for Greg Toland to shoot Citizen Kane. Another early BNC was sent to the Soviet Union for Eisenstein’s Ivan The Terrible, released in 1944. From the mid-1940s to the 1960s, Paramount won more than 70 Oscars. Every one of them was shot on a Mitchell BNC.

Camera engineer George Mitchell started making cameras in 1920. By 1925, he had a mechanism that could shoot steadily at 128fps. At the heart of the BNC was the famous and beautifully designed Mitchell movement with double claws and register pins, rock-steady, reliable and quieter than other cameras at the time. The BNC had a rack-over viewfinder system, based on a design by cameraman John E. Leonard. This meant the body of the camera with the film chamber was moved out of the way so the operator could check focus and framing on a ground glass screen. When satisfied, the camera body would be racked back in place and the operator would switch to a side-finder to view the shot. This system would continue to be used well into the 1960s.

The same weight as twenty ARRI Alexas

Mitchell designed and built the movement that was at the heart of the massive 1932 3-strip Technicolor camera, then described as the Rolls Royce of cameras. In its blimp, the Technicolor camera weighed close to 500 pounds (that’s the weight of around twenty Alexa 65 cameras) and, in today’s money, cost almost half a million dollars.

The acronym ‘BNC’ actually stands for ‘Blimped Newsreel Camera’, but news is the last thing we would associate with this huge, heavy camera today. No way could you hand-hold a Mitchell – it took two people to mount it on a tripod. The coming of sound had a drastic effect on the size and weight of cameras. The ‘blimped’ part of BNC meant the camera mechanism was built inside a soundproof casing, aided by the quieter Mitchell movement, and although this resulted in a very large camera, it was small and portable compared to the soundproof booths that cameras lived in at the start of the talkies.

The Mitchell not only dominated movie production in the post-war era, it was also the camera that was used on a multitude of American TV series. The Mitchell movement was also at the heart of the widescreen VistaVision (35mm film running horizontally) and Todd-AO (65mm) cameras of the 1950s. In 1967, the BNC finally became a reflex camera – the celebrated BNCR. The Mitchell movement was also the basis of the Panavision cameras which would dominate cinema production for the rest of the century and are still widely used today.

An essential part of cinematography

The fact that the Mitchell movement could be an essential part of cinematography for so many decades is not only a testimony to George Mitchell’s superb engineering but also, perhaps, to our continued fascination with the mechanical in the digital era. If you covet an expensive Swiss watch, it is sure to be a mechanical design, even though the digital clock on your phone or almost any gadget in your house probably keeps better time. We love film cameras in a way it is hard to love digital ones. They are physical and tactile, we can understand how they function just by looking at them, whereas digital processes will always remain invisible and remote. Movie cameras are beautiful things. This is part of the reason, I believe, as much as picture quality, that 35mm film has survived well into the 21st century.

It is interesting that, throughout the history of filmmaking – while there are filmmakers pushing technology to make cameras lighter and more portable and crews smaller (Super16, digital cameras, smaller formats) – there is an opposite tendency that makes cameras more sophisticated, resulting in larger cameras and larger crews (3-D, larger formats, separate recorders). The movie industry tends to be conservative in relation to new technology. This is understandable, as producers want to limit risk in an inherently risky business and crews want equipment that is familiar and totally dependable. Large cameras mean large crews and let’s be honest, people, quite reasonably, want to hang on to their jobs. There is no denying the Mitchell was a superb camera and a whole way of working has grown up around it, but it is worth asking the question how it maintained its position for so long when new technology was creating cameras that were smaller, lighter and more versatile. This is a question we will pursue in the next part of this story.

It would be great to hear from readers who have actually worked with the Mitchell – please tell me your story, and of course, correct my mistakes!

tl;dr

- The Mitchell BNC emerged in the 1940s as a dominant studio camera, significantly influencing Hollywood filmmaking during its golden age and contributing to numerous award-winning productions.

- Designed by camera engineer George Mitchell, the BNC featured a sophisticated mechanism known for its stability and quiet operation, enabling filmmakers to achieve high-quality sound in their productions.

- Although the BNC was originally designed for newsreel production, its blimped soundproof casing and substantial weight made it a staple for both movies and American television series for decades.

- The lasting impact of the Mitchell movement can be seen in its adaptation for various film formats and its influence on subsequent camera designs, highlighting a continued appreciation for mechanical film cameras in an increasingly digital world.