The upcoming Panasonic HC-X1

The upcoming Panasonic HC-X1

ENG cameras have changed a lot in the past few years and nothing exemplifies the new breed as much as Panasonic's recently announced HC-X1 4K/UHD ENG camera - a unit packed full of features and capabilities being released this month for a meagre $3199.

ENG cameras have changed a lot in the last few years. We're not talking about the increasing tendency for even quite high-end current affairs programming to be shot on handycam-style devices; that's been a trend for more than a decade, on the basis that the downsides are more than outweighed by sheer portability. The difference is the move to 4K and the concurrent move to big-chip (or at least bigger-chip) cameras.

The big chip ENG field

These cameras are made very differently to a traditional news camera, although those changes aren't necessarily all that obvious from the operator's perspective. Big-chip news cameras are typified by things like Sony's PXW-Z150 and PXW-Z70, the latter of which is a very small camera with a comparatively large slab of silicon behind the lens. Compare the entirely different approach of the two-year-old PXW-X180, which uses three one-third-inch chips in a more conventional configuration of one sensor per RGB channel to produce HD images. The PXW-X180 doesn't feature 4K recording, but the application (news) and the handling (reasonable) are comparable.

Competing directly with the PXW-Z series is Panasonic's AG-UX series, such as the AG-UX180, which offers a one-inch chip, 4K pictures and a servo lens with firmware that makes it really good for its class. We considered its little brother, the UX90, in a previous piece and, with the lens set to 'coarse' mode, it behaves much more like the lenses that news people are used to operating on much bigger, heavier cameras. No servo lens will quite have the positivity and directness of a real mechanical zoom, of course, but it's remarkably good.

The 8.8mm wide end of the Leica-branded lens is usefully wide.

The 8.8mm wide end of the Leica-branded lens is usefully wide.

The UX180 enjoys an 8.8 to 176mm zoom lens, while the UX90 doesn't go quite as long, being limited to a 15x optical zoom from 8.8 to 132mm. The wide end, for news, is often key: many people would smirk at a camera which only offered an 8.8mm wide end on a 2/3" chip broadcast camera, but on a one-inch sensor, it's a nice broad field of view. People have complained that it doesn't quite keep up with the very widest broadcast zooms, which sometimes play in the under 5mm range and are useful in tight press packs, but it's certainly a lot easier to build an 8.8mm lens for a single one-inch chip than it is to provide an equivalent field of view across three third-inch sensors.

The other reason for the big sensors in 4K cameras of all stripes is physics and the desire for low-light performance. The bigger the light sensitive areas on the sensor, the more photons are likely to hit them during the exposure. Pixel size matters and, while it's clearly possible to fit 4,000 or so of them across a third-inch chip, it's not necessarily that great an idea. Doing that makes for tiny photosites that lack sensitivity, provoke noise and limit dynamic range. It's much better to use a larger sensor, fit more photosites across it and enjoy better low-light performance, particularly as regards colour reproduction which can really suffer on less well-engineered sensors when there isn't enough light. This is often what's really wrong with cellphone video, among many other things.

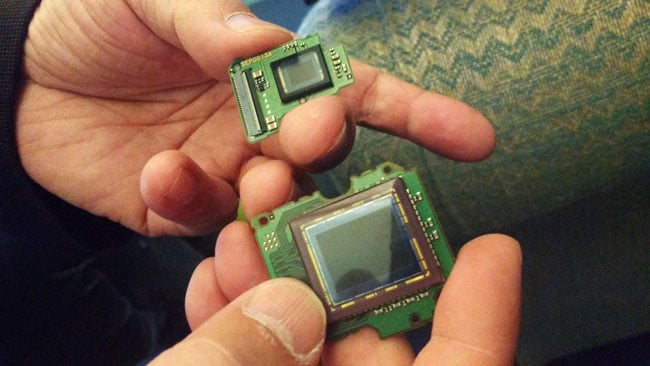

The difference between sensor sizes is clear when they're viewed as components.

The difference between sensor sizes is clear when they're viewed as components.

A contender on the horizon?

These, then, are the considerations which drive the adoption of larger sensors in modern 4K ENG cameras: lens design and sensitivity. The AG-UX180 sells for something like £3500, offering a somewhat greater zoom range and higher 4K frame rates over the rather cheaper Sony PXW-Z150. A deal that's better than either, however, is the upcoming Panasonic HC-X1, which appears to all practical purposes to be an AG-UX180 shorn of its SDI port and, at about $3199 / £2400, it's very considerably cheaper. The utility of the SDI output is dependent entirely on the job at hand; people who need to be able to shoot news and patch up to a satellite truck will need the SDI. Otherwise, the HC-X1 looks like a really good deal.

It's controlled and distributed by the domestic camera department, rather than the professional arm of the enormous conglomerate that is Panasonic, but the specification is incredibly similar to the UX180. It has the same 20:1 lens with that useful 8.8mm wide end, not the cut-down 15:1 zoom of the UX90, and the excellent 'coarse' drive mode is retained in the lens options. It retains the optical image stabilisation and all of the double-slot recording tricks. There are differences (very possibly dependent on location) in the warranty arrangements, but otherwise the two models are practically interchangeable.

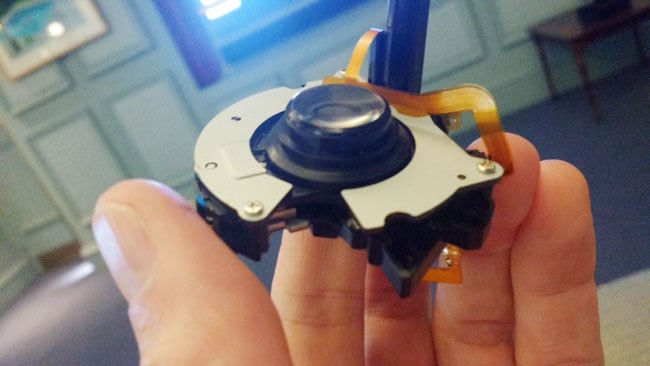

At their London meeting, Panasonic showed some internal components of the camera.

At their London meeting, Panasonic showed some internal components of the camera.

This is the optical image stabiliser.

The model numbering suggests that the HC-X1 is being positioned as a big brother to the HC-X1000 4K camcorder, which really serves to highlight the gigantic gap between them in terms of specification. The company's recent presentation in London made much of the X1's low-light performance, which is genuinely and noticeably better than smaller-chip designs, as well as the optical and electronic image stabilisation which, when used at full capability, is very effective. The autofocus modes are also pretty useful, using an approach of frequent micro-adjustment which seems to keep things sharp with only very minor artifacts. Also, there's excellent image stabilisation. In full 4K mode, it's entirely optical (the hardware is pictured above), but in certain modes, there's enough free space and spare resolution on the sensor to produce five-axis image stabilisation. In these modes, the camera can tune out not only instabilities of pitch and yaw, but also the roll axis and both horizontal and vertical perspective distortions. Nothing like this is ever perfect and it can look slightly laggy in the right, or wrong, circumstances, but it's more than good enough to be useful.

As on the UX90 and UX180, all the buttons are in the right place.

As on the UX90 and UX180, all the buttons are in the right place.

Assuming equivalence with the UX180, video is recorded as 4:2:0 8 bit, which is perfectly adequate for current affairs, especially at 4K. The lack of a log recording mode will frustrate people looking for a crash camera to use alongside something like a Varicam 35, but upcoming additions to the GH mirrorless stills camera line are likely to better satisfy that desire in any case. The cine-like modes, which represent something of a halfway house in terms of prioritisation for dynamic range and contrast, are retained from the UX180. There is presumably some desire not to cannibalise the DVX200's market here, but it's a very respectable feature set for what's being unequivocally positioned as the little brother to a news camera.

All of the cameras we've talked about here are horses for a reasonably specific course: news and current affairs, high-mobility documentary, weddings and other circumstances where discretion and portability are key. The question really is why Panasonic has chosen to be so generous. For a certain fairly small group of people, the lack of an SDI port will be a concern. For everyone else, the cost saving of the HC-X1 over the UX180 makes the X1 look like an absolute steal.

Tags: Production

Comments