As fast as a Lamborghini with Ludicrous Mode engaged

As fast as a Lamborghini with Ludicrous Mode engaged

RedShark Replay: Trying to use a camera designed for taking stills for serious video shooting is like trying to drive a Telsa electric car in Ludicrous Mode all the time. Eventually, something will probably break. It’s all a question of purpose, design, architecture and economics. [Opinion]

You’ve probably heard of electric car manufacturer Tesla’s “Ludicrous Mode”. It’s a setting you can select for your Tesla that will allow you to channel the maximum possible power to the electric motors to give an absolutely stupendous performance. Tesla’s Model X SUV, which is at least in name a Sports Utility Vehicle can outpace supercars in its Ludicrous Mode.

It’s all very impressive, but completely unrelated to the basic task of being a highly usable electric vehicle for all the family. Practically going into orbit is not on the list of requirements for a typical family load-lugger. Not that the Model X is typical in any way.

I’ll come back to Tesla in a moment.

Meanwhile, I’ve been talking to a few people lately including some I respect greatly - about still photography cameras that can be used for video. Specifically, we’ve been mulling over the tendency of some of them to overheat and even shut down after prolonged video use. Some people think this should never happen. I think it’s a nuisance, but not even surprising when you look at two things:

1) These are still cameras, or, to put it another way, these are cameras that are designed for still photography that can nevertheless shoot video.

If you’re a video maker, you may not realise that still photography isn’t just a bigger marketplace for camera manufacturers, it’s massively, hugely bigger. A couple of years ago at the IBC show in Amsterdam, I remember being impressed at the sheer size of the Canon exhibit. A few days later I was in Cologne, at the world’s biggest photography show, the Bi-Annual Photokina. I didn’t measure it, but Canon’s exhibit seemed like it was ten times the size of the IBC one.

If nothing else, this should teach you that when a still camera also does video, it’s very much an “also”. While it may not be fair to call it an afterthought, it’s certainly not the primary tag by which the cameras are intended to be sold.

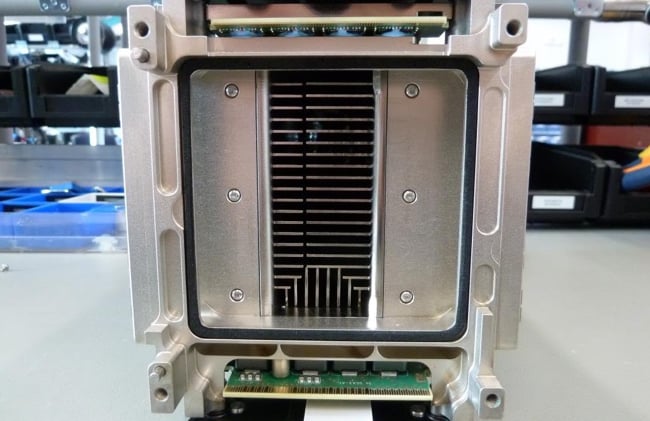

Massive heat management inside an ARRI Amira

2) When you look at cameras that are primarily designed for video, they mostly have fans. They all have heatsinks. Most have both, and some, like the ARRI Amira (above), are architected entirely around heat management.

Still cameras don’t usually have fans. This fact alone should make it less surprising that they sometimes overheat when shooting video. (I acknowledge here that the issue isn't necessarily limited to video. Some still cameras can overheat when in "Live View" mode for long periods.)

Tesla’s Ludicrous Mode

If an electric car’s main purpose in life is to save energy and make its batteries last as long as possible, then it is at least reasonable to suspect that it is not really going to be designed to run at full pelt all the time, or even a majority of it. I’ve been in Teslas. I haven’t driven them and certainly not in Ludicrous Mode. But what I have heard is that you can’t keep the electric car in the super-boosted mode for long or indeed repeatedly, because things overheat and generally get out of shape. This is completely unsurprising. It’s a party piece, and an extremely effective one. It’s a marketing department’s dream. Who doesn’t want a car with zero emissions that is faster to 60mph than a Ferrari?

But nobody expects to be able to drive it like that all the time. Probably, most people understand that, and very few people complain.

How does this relate to cameras?

At least partially, I think.

For a still imager, shooting 4K video, possibly at high frame rates, is like the Ludicrous Mode for that camera. It is certainly somewhat different from the Tesla example because nobody, I suspect, buys a model S or X to spend all day in Ludicrous Mode. Lots of people buy still cameras to shoot video. If you buy a still camera with a video mode, it’s reasonable to expect that you will be able to take and make videos with it. But its also reasonable to expect that because of the price, design and architecture of the camera, there may be limitations in comparison with cameras whose sold purpose is making video.

Consider this: with still photography, you’re either taking single shots or at the most a few tens of shots in a burst. This doesn’t tax the system thermally (unless you're in continuous "live view"). But when you switch to making video, you’re asking a very different question. You’re expecting the camera to shoot maybe 60 fps at 4K or above resolutions. Not just the sensor but the camera’s digital electronics will get hot. Real-time downsampling from tens of megapixels is very compute intensive. And if they have to process 60 frames per second instead of one or two, for extended periods, without extensive thermal management (another phrase for heatsinks and fans) something has to give, at some point.

So it’s all a question of purpose, design, architecture and economics. If you expect a camera who’s main purpose isn’t to make video, which has been designed around the needs of still photographers, has a different architecture to one that would be optimal for video makers, and which is perhaps one twentieth of the price of cameras that it can so nearly emulate in picture quality, then it really would seem that you shouldn’t expect the cheaper devices to ultimately be as good as the dedicated video camera in at least some respect.

If you want to shoot a movie on a still camera that also does video that’s fine. It’s rare for movies to have continuous shots more than a few minutes. If you want to shoot a concert performance - well, don’t be surprised if there are heat issues.

There are ways round this. For example, if your work is impacted by a heat management issue, buy two of the cheaper cameras and rotate them. Shoot with one while the other is cooling down. We all know about the other ways to shoot professionally with stills cameras that have a video capability: rig them up. Make them ergonomic. Put external viewfinders and recorders on them.

Do any of this stuff. It’s fun and it’s practical. It’s alternative. This is all good. This has brought cinema-quality video to a demographic (which could also be called “the majority) that has never had access to this level of videomaking before. Buy them for remarkably little money, marvel at the near-miraculous quality of the pictures, and enjoy being a filmmaker.

But also remember the origins of these cameras and the still photography marketplace where they sell in enormous volumes.

And if none of this appeals to you, then you still have the option of buying a dedicated video camera.

Tags: Production

Comments