Replay: Freelancers are often expected to supply their own batteries, cables, stands and more, and thus often rack up expenses that are never billed.

If you're someone who regularly fills in gaps on shoots with personal equipment (and if you rarely get paid for doing that), you probably know where we're going with this one. If you're someone who regularly works with freelancers who have a lot of personal gear, well, if you were referred to this piece by one of them, that might be worth a second thought. This is an article about comparing what gear appeared on the invoice with what gear appeared on set and what it did for the production. But it's also about making oneself maximally useful, investing in the sort of thing that keeps one useful for the maximum possible amount of time.

Gear that's taken for granted

The sad reality is that nobody has ever been amazed by, say, batteries. Or cables. Or tripods. Or lighting stands. Even a huge box full of tungsten fresnels tends to be shrugged at these days, having committed the cardinal sin of not being LEDs. People get hired for the camera they own or, if they're very lucky, because they're mates with the director, not because they happen to have a battery charger and a toolbox with a spare mains fuse for it.

(I have heard tell of historical circumstances under which camera crew were occasionally employed on the basis of their expertise behind the camera, but such circumstances clearly only deserve this parenthetical mention in a modern context.)

All joking aside, nobody ever got hired because they owned, let's say, half a dozen C-stands.

Combo stand. Cost: lots. Awesome factor: near zero.

Combo stand. Cost: lots. Awesome factor: near zero.

Of course, the reality is that half a dozen C-stands of even the low-priced, knocked-off variety, is over a thousand pounds' worth. It's just about as costly to put together a reasonable battery system capable of powering professional film and television cameras, especially as the lower-cost cameras – Blackmagic being the key example – tend to have higher power consumption and especially because lower-budget productions are less likely to enjoy continuous access to mains power.

Cables, though, have perhaps the most alarming ratio between their visible awesomeness (near zero) and their price (often lots). An Atomos Shogun, for instance, has its audio inputs on a 1B-series Lemo connector. A compatible Lemo FGG.1B.310 connector alone runs at £25 plus VAT. A complete cable assembly is often priced beyond £100, and you need one, because the one Atomos supply is usually too short. Plus postage and packing, that's the cost of a rather nice meal out for two that you're never going to see again (and nobody is ever going to be bowled over with amazement at your ability to plug a microphone into a recording device).

DisplayPort is one of many standards for which one might be expected to own a series of £15 cables.

DisplayPort is one of many standards for which one might be expected to own a series of £15 cables.

Okay, nobody goes into film and television camerawork, or indeed plumbing, without the understanding that it can involve a lot of owner-operated equipment. At all levels, some people find it interesting specifically because of that; gear acquisition syndrome is common in film crew and it is a complaint most commonly suffered by people who have a certain propeller-headed enthusiasm for blinkenlights.

At some level, though (and all too frequently in the microbudget world), it's incredibly easy to roll up to a shoot with the best part of five figures in unspectacular but highly necessary gear that too many directors seem to assume just simply exists somehow, without too much concern as to where it comes from or much interest in paying for it. How often have we used a personal laptop as an offload device, in the absence of a digital imaging technician who might expect to draw both a wage and an equipment rental fee – and are we undermining each other by doing these things?

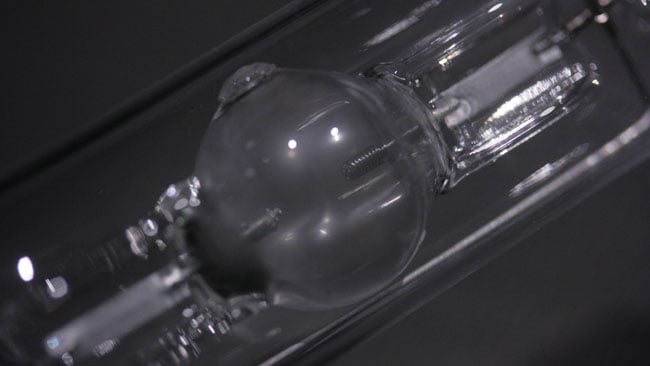

Spare lightbulb. Value about £90, but nobody cares until it blows.

Spare lightbulb. Value about £90, but nobody cares until it blows.

Did the money ever really exist?

And that, of course, is really the point. Some productions genuinely can't afford certain things and we may make our own lives harder by keeping otherwise idle gear off set. There are a thousand other extenuating circumstances. Lending out gear is a great way to repay favours. Discounting it is an easy deal sweetener. All of these things work best if there's a pre-existing relationship with the lendee, which, as we've said before, is often a greatly moderating factor when working for free.

At some point, this raises a question about intent. A lot of very low budget shoots rely heavily on what's basically charity in order to be even vaguely feasible. There are, of course, genuine moments when a good cause is to be helped, and that's another matter entirely.

PAR lenses. Four required per light. Often seen as an irritating extra to lug around.

PAR lenses. Four required per light. Often seen as an irritating extra to lug around.

Otherwise, though, our willingness, as individuals, to continue funding other people's art is key to the whole equation and one we'd all do well to be aware of, no matter how much fun we're having into the bargain. The culture of free is endemic to a level that's probably already unsustainable in cheap filmmaking. Let's not sleepwalk into making that even worse.

The upside to all this is that some of the most invisible equipment are the best and longest-term investments. Batteries can be recelled and go on for decades. The development of evermore various varieties of video interconnect notwithstanding, general-purpose cables are likely to work the same way. Lights, at some point, are lights, and the stands they go on especially so.

Putting all this gear on the invoice at a reasonable rate and discounting its rental value at the end is one way to make the situation clear, but ultimately there's almost no real way to make the value of personal giveaways clear to producers (or more often producer-directors) without risk of looking like the bad guy.

So, make the decision for good reasons, smile, and pull the flight cases out of the car. It'll make you look good.

Tags: Production

Comments