How to create a look without going digital

How to create a look without going digital

Redshark's only 10 months old, and our readership is growing all the time. So if you're a new arrival here you'll have missed some great articles from earlier in the year

These RedShark articles are too good to waste! So we're re-publishing them one per day for the next two weeks, under the banner "RedShark Summer Replay".

Here's today's Replay:

Here's how to make your films look good

You don't have to rely on digital methods to give a film a distictive "look". Phil Rhodes explains..

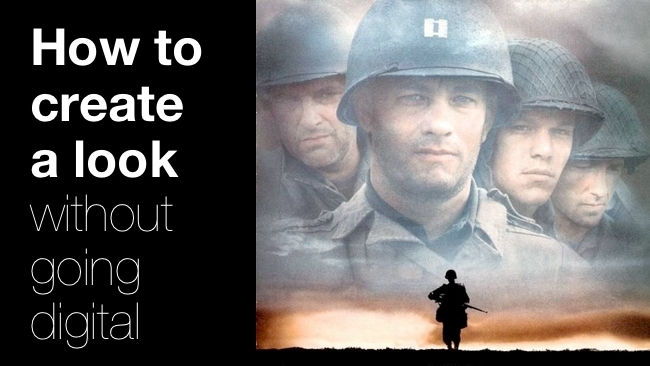

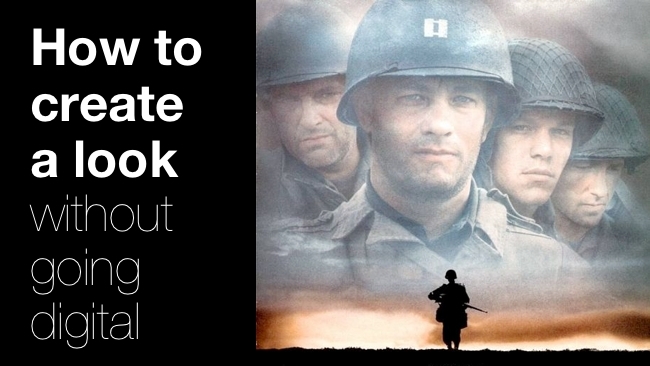

There was a time – around the release of The Matrix and Saving Private Ryan, in the late 90s, where green was somehow in. Posting on a cinematography forum at the time was to be assailed from all sides with requests for information on how this was achieved, invariably concentrating almost exclusively on the subject of film stocks, processing, cameras, lenses, and grading, and how they were used and modified to make these movies look the way they did. This sort of inquiry is made in respect of all kinds of film, but particularly those with a very overt and identifiable visual style, such as the inevitable teal-and-orange of the summer action movie, or the cool white crispness of an accomplished science fiction such as Minority Report.

The case of Ryan

Particularly in the case of Ryan, this isn't necessarily an unreasonable line of enquiry. The film famously used bleach-bypass processing to increase contrast and decrease saturation, and cinematographer Janusz Kamiński had the coatings stripped from his lenses to create flare and softness intended to approximate period optics. Narrow shutter angles were used to limit motion blur, creating a staccato look to fast movement that's particularly visible when an explosion throws debris into the air, and it comes raining down. The shutter timing was deliberately slipped, notionally blurring the entire image vertically as the film begins to move while the shutter is still open, but as a practical matter visible mainly in highlights such as live flame. This last technique became so popular that Arri eventually released the Timing Shift Box for the Arriflex 435 Advanced camera, which had always been capable of in-shot shutter angle changes in order to compensate the exposure of speed ramps. With the TSB, it became easy to duplicate the effect used in Spielberg's film, or even to add random or manually-controlled fluctuations to the extent of the effect.

Saving Private Ryan was a fantastic-looking movie, and won the Academy Award for best cinematography, as well as being nominated by the ASC for their outstanding-achievement award. It was, you might say, an extremely camera-oriented film, and the technical approach had an influence on these successes that's noticeable to the layperson. But here's the thing. If you look (which you easily can, via google) at behind-the-scenes stills shot during the production, which were shot on conventional colour stills film and did not use any of these specialist techniques, you'll discover that it still looks quite a lot like Saving Private Ryan. Okay, Photoshop may have played a part in that, but the main reason for this is something that I don't think independent filmmakers talk about nearly enough: production design.

Production designers

Filmmaking is, famously, a team sport, and I'm sure that cinematographers working on high-end shows (or, in fact, any show) would be happy to acknowledge that the way the look of the thing is influenced at least as much by the choices of the production designer as it is by those of the cinematographer. Of course, people in these roles ordinarily confer extensively to ensure that a cohesive vision is achieved, but still, this is a principal reason why the advent of digital cinematography hasn't really made a huge difference to the budgets of really big movies. Achieving a visual result that satisfies summer action movie audiences still requires expensive production design. Sets must be built and locations found that not only serve the story and facilitate the required action, but which are sympathetic to the production designer's intent. Science-fiction and fantasy films are notoriously demanding and likely to require a huge proportion of the costumes, environments and objects that will be seen to be designed and built from scratch. These are factors that are completely independent of the recording medium.

One of the principal techniques in use here is colour control. To continue our examination of Saving Private Ryan, it's easy to identify the fact that since everyone's in the army, they're all wearing green, and it was shot to look like France in June (the date of the real D-day landings), so the locations are frequently green with foliage as well. Much of the time, the sky is overcast, and thus so is the sea. The ruined French village seen during the film's climax was built from scratch, without the use of saturated colours. The film may well have looked green and desaturated when viewed in the cinema, and it may have used techniques of cinematography to enhance that intent, but ultimately it was already green and desaturated, before a camera went anywhere near it. Complain as we might about the excessive use of teal and orange, it's done for simple reasons: human skin tones are generally warm colours, and the sky, moonlight, is often rendered as blue. These colours are naturally present in many scenes and approximately 180 degrees apart in hue, allowing the production to satisfy a fundamental principle of good visual design without having to paint everything odd colours.

"You can only shoot what's in front of the camera"

People who are involved in camerawork talk about equipment a lot and it's not surprising that they do. I'm not here to tell anyone that factors like sharpness, noise level, and dynamic range aren't important; quite the contrary. Distracting noise or excessively clipped highlights are the things we're lucky to be moving away from. But these things are important in a different way than production design, or other frequently-overlooked things like filtration and entertaining devices such as Arri's Varicon, which bleed a certain amount of light into the whole frame, akin to flashing. Filtration works just as well on video as it does on film. But regardless of what you put behind the actors, hang on them, or place in front of the lens, regardless of whether you're working with miniDV or IMAX, you can only shoot what's in front of the camera.

And to the Matrix and Saving Private Ryan fans out there, I'll answer the question the same way I have many times before. How do you make it look green?

Shoot green objects.

Tags: Production

Comments