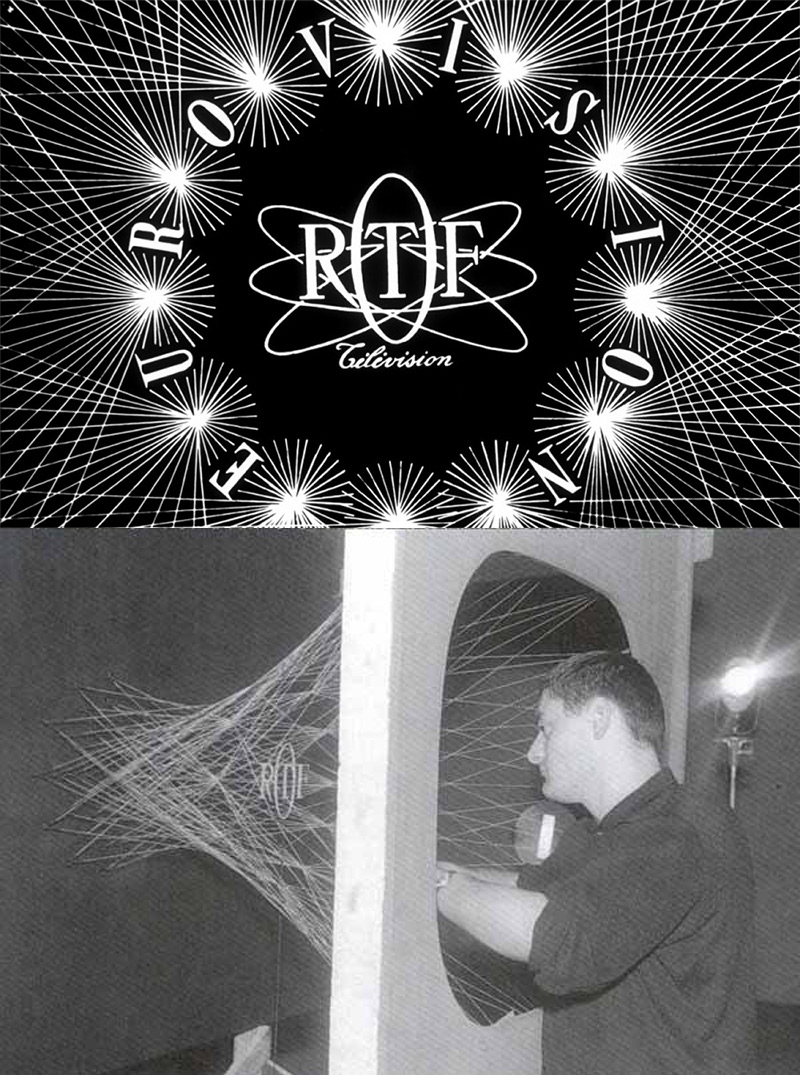

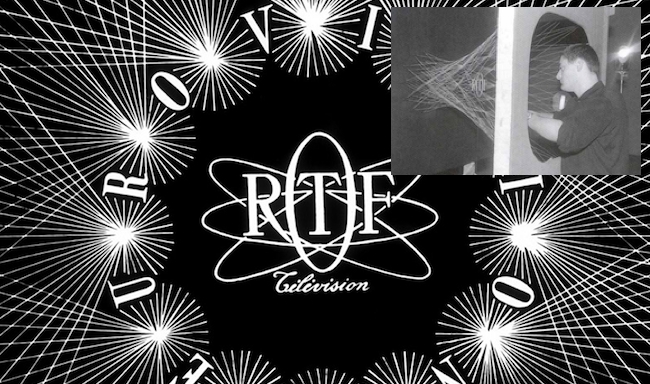

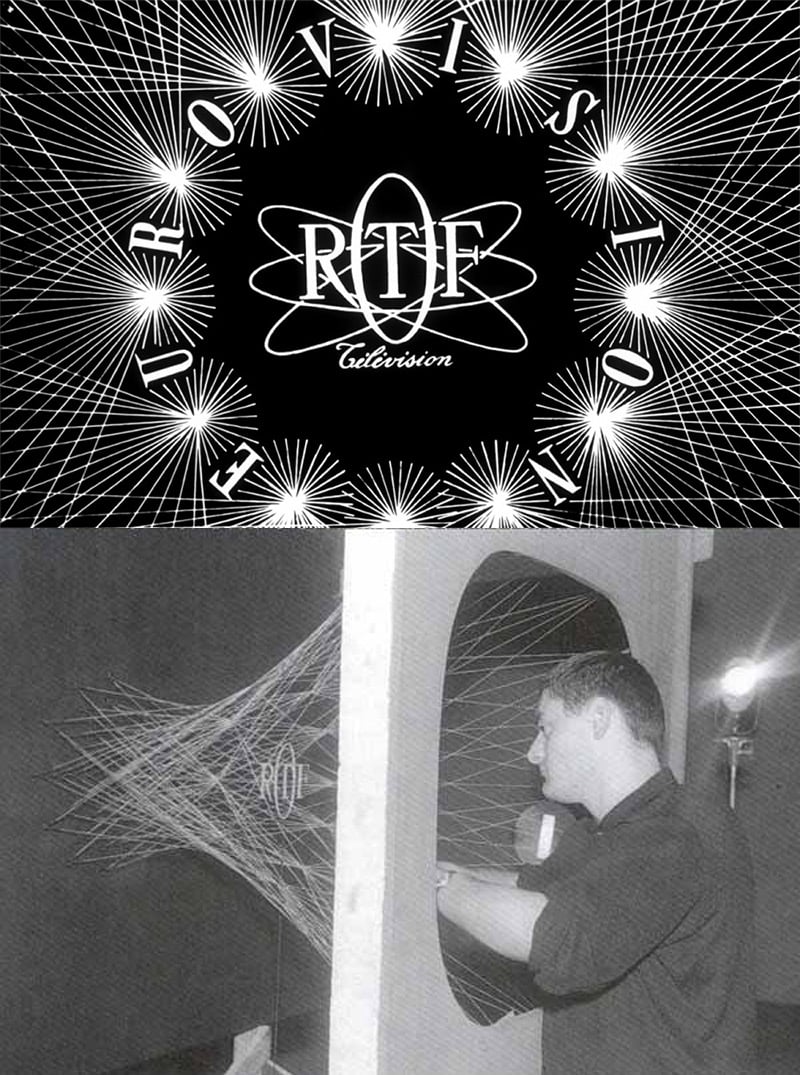

How it used to be done: a logo made of card and string

How it used to be done: a logo made of card and string

Now, *this* is how to create a TV ident. Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française's original Eurovision logo was mixed in live from a camera pointed at a cat's cradle of string. Phil Rhodes reckons the all-pervasiveness of CGI means we've lost something along the way.

There's a widespread reaction against the excessive or lazy use of CGI. In part, it's because of what we might call the Green Lantern effect, a side-effect of stuff that just doesn't look that good. It's not just that, though. Lots of CGI looks great and allows people to do hitherto unimaginable things. The thing is, as the continued market for oil paintings and high-end sports cars indicates, people like craftsmanship for its own sake. It's a bit unfair to characterise computer generated images as lacking craft — Green Lantern notwithstanding — but there's certainly room for doubt in a world where the most recent Rambo movie insulted us with digital blood at the sub-Playstation level.

If you find yourself identifying with any of this and if you have any interest in motion graphics, there's probably some joy to be found in the TV logo techniques of yesteryear. The spider's web tangle of the Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française Eurovision logo is somehow recognisable even from an oblique angle and the curved mirror behind a globe that created the 1980s BBC ident is fairly well known.

How it was done in the really old days...

The techniques behind the classic HBO “city” bumper are likely to provoke rather more conflicting feelings. The degree of craft on show is peerless, from model making to rostrum camera animation techniques and motion control, with a lot of work on the optical printer to combine everything. What's slightly off-putting about it is that there's a piece of flying text, a chrome HBO logo in space, which is precisely the sort of effect beloved of early computer imaging people. It looks very much like a piece of early CGI, right down to the way the ersatz reflections don't really match the environment it's in. Actually, they opted to shoot the chrome logo by making a logo in chrome and shooting it.

Programming motion control moves is similar to creating a camera move in software. The difference is the two-ton industrial robot which whirs into action and smashes the model to pieces if misdirected. They're still used for tricks such as the combination of conventionally shot live action with time lapse, or a flawlessly ramped move that lands precisely on a mark. What's impressive about HBO's work is that there are no obvious reflections of camera or grip equipment in the chrome. We might imagine longwinded iterations of moving black and white flags around to achieve the spotless results we see.

HBO's flying logo is arguably one of the less interesting elements because it was done at a time when the techniques were well-established. Creating a set of flawless chrome letters is a task not to be underestimated (watch the guy brushing the dust off it) and it was done at least twice, as the lettering under construction early in the behind-the-scenes piece is not the lettering in the final product. Perhaps more illuminating (ha) is the fibre-optic rig built to do the streak effects, which resemble CG but, again, aren't. It's not clear whether that particular rig was custom-built for HBO's production, but the effect is reminiscent of contemporary work such as that done by Steven “Tron” Lisberger and his studio.

Tron is a great point to end on. As someone says in the DVD extras, the necessary visual effects work had never been done that way before and it will never be done that way again. There is discipline in difficulty, though it's probably excessively puritanical to suggest that the process of sending endless rotoscoping to Korea, as was done for Tron, is particularly beneficial to the process of storytelling. What's certainly true is that the embarrassment of riches represented by the excessive application of CGI to modern filmmaking has cost us something.

Especially if we're talking about Green Lantern.

Tags: Post & VFX

Comments