SpaceX’s Starlink system moves out of beta next month and promises to provide broadband connectivity via satellite anywhere in the world.

As is the way of these things when you’re dealing with a maverick like Elon Musk, news that SpaceX’s Starlink service was going to finally move out of beta and go live next month was broken in a slightly tangential manner. Twitter user @Overshield sent him a message asking him when it would happen, he replied ‘next month’, and various sections of the internet duly caught fire.

Given that such things usually happen at a fairly glacial pace, the set up of Stalink has happened phenomenally quickly. Designed to provide broadband connectivity via satellite to remote regions where ISPs will either not go or simply don’t exist, Starlink was announced in January 2015 and the launch of the first constellation of 60 satellites took place in May 2019 via one of the company’s Falcon 9 rockets.

These launches have since become a rapid favourite of sky watchers for the distinctive beaded pattern, the Starlink train, the individual satellites make as they slowly separate and move to their eventual orbital positions. There have been a lot of them too.

As of Monday 12 September there are 1791 Starlink satellites in orbit, but that’s only the start. SpaceX has a license from the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) to launch 12,000 Starlink satellites in various different orbital shells and is currently seeking to expand that number to 42,000.

The satellites

The concept of Starlink relies on a mesh of satellites whizzing around in Low Earth Orbit (LEO), which is usually defined as anything between 160 to 2000km above the Earth’s surface — Starlinks’ initial shell is at 550km. They are almost totally the opposite of the first telecommunications satellites which were placed in Geostationary orbits at 35,786km (also know as the Clark Orbit after the science fiction writer Arthur C Clarke who first helped popularise the concept in 1945) where they naturally orbit above a fixed position on the planet below.

Because LEO satellites pass over the ground beneath them so fast, orbiting the earth every 90 minutes or so, they need to hand-off any signal with a ground station from one to the other as they orbit. That’s why you need to many to ensure coverage. They also have to be thought of as technically disposable; anything in LEO orbit is subject to atmospheric drag and will eventually fall back to Earth in fiery ruins, with even large objects such as the eventually doomed Hubble burning up in the atmosphere.

So why use them? There are a few very good reasons. The satellites themselves are smaller and cheaper, meaning you can make them quickly (SpaceX has been producing up to six a week) and fit more of them in a single launch. And that lower orbit also reduces network latency, allowing for more of the sort of two-way functionality that broadband provision demands.

The service

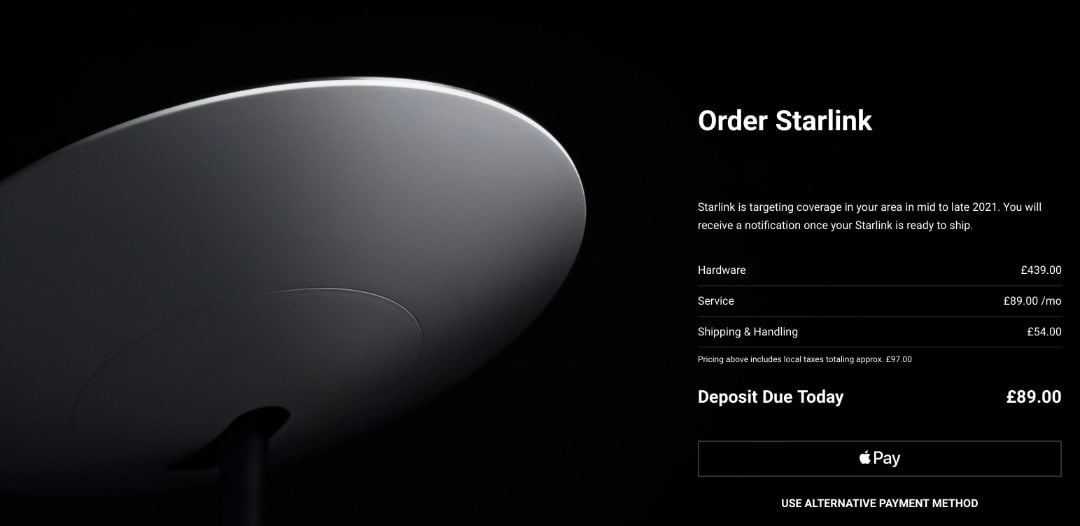

So, what do you get with Spacelink and how much do you pay for it? For $499 (£439) you get a Starlink Kit that includes everything you need to connect to the internet including your Starlink dish, wifi router, power supply, cables, and a mounting tripod. The mounting tripod is designed for ground level installation, or to support a quick start setup to test your internet connection. Roof installation is a separate cost.

Don’t forget that you’re not trying to pinpoint a geostationary satellite somewhere, so as long as you have clear field of view around the dish — a 100-degree cone around the centre of the dish (after tilting) with a 25 degree elevation minimum — you don’t have to be exact with its positioning.

That coverage will get better as more satellites are added to the constellation, but for now the company advises that users who live in areas with lots of tall trees and buildings may not be the ideal early adopters of the service.

As for speed, the company reckons that 50Mbps to 150Mbps and latency from 20ms to 40ms in most locations is the current ballpark. For that you pay $99 (£89) a month.

As anyone who has suffered down one of the many cul-de-sacs at the fringes of the information superhighway and will offer you their firstborn for bandwidth will tell you, it’s pitched fairly well; by our reckoning around double what you would pay for a high bandwidth fibre connection in an urban area.

It’s not ‘internet for the masses’, but it is internet pretty much everywhere. And the prices will probably fall as the service scales. Equally tiered pricing structures with differing service levels are fairly likely in the near future.

Talking of which, availability is likely to be an issue, however, at least for that period. SpaceX says it has been servicing 100,000 users during the beta, and has pre-orders now totalling 600,000 and counting. That’s going to need more birds in orbit. Meanwhile, it is looking at expanding the number of users the FCC will let it support in the US from 1 million to 5 million.

Our unscientific analysis of the situation — me starting a dummy order for where I live on Belfast Lough in Northern Ireland — suggested that the company is hoping to get this part of the world connected by the end of the year.

Other constellations are available

While Musk and SpaceX’s well oiled hype machine tends to push it firmly into the centre stage, Starlink is, of course, not the only satellite constellation looking to provide internet capability. Amazon is planning to launch half the satellites of its Project Kuiper system — a mega constellation of 3,236 satellites — by 2026, and bizarrely the UK government has invested in a bankrupt space internet mega constellation company OneWeb, which to date has the second highest number of satellites in orbit behind SpaceX (218 at last count).

These join existing satellite internet services built out of geostationary orbit such as Viasat’s Exede. There is also interestingly an already working MEO (Medium Earth Orbit) service provided by SES called O3b which is about to get expanded with the launch of the O3b mPOWER satellites. MEO allows for the company to maintain global coverage with a mere 11 satellites, and represents a half way house neatly balancing the advantages and disadvantages of geostationary and LEO options. Up till now, however SES has been more interested in chasing the business market than the consumer one.

There are objections to Starlink. Astronomers have expressed disquiet about the increasing amount of stuff whizzing about in LEO in general, to which SpaceX has responded with what it refers to as ‘a darkening treatment’ which seems to have had some success. And, as increasingly seems to be the form with billionaire-backed projects, Amazon has objected to any expansion of Starlink’s FCC license.

But for now, the launches continue, with a Falcon 9 being prepped on a launch pad at Cape Canaveral to launch another Starlink train into orbit before the end of the year. Can Elon Musk solve the problem of broadband everywhere? At the moment, it looks like he will.

Tags: Technology

Comments