Jupiter has probably never looked quite as good as it does in the latest photo from Webb’s extraordinary and growing collection of images. And it was an amateur that put it together.

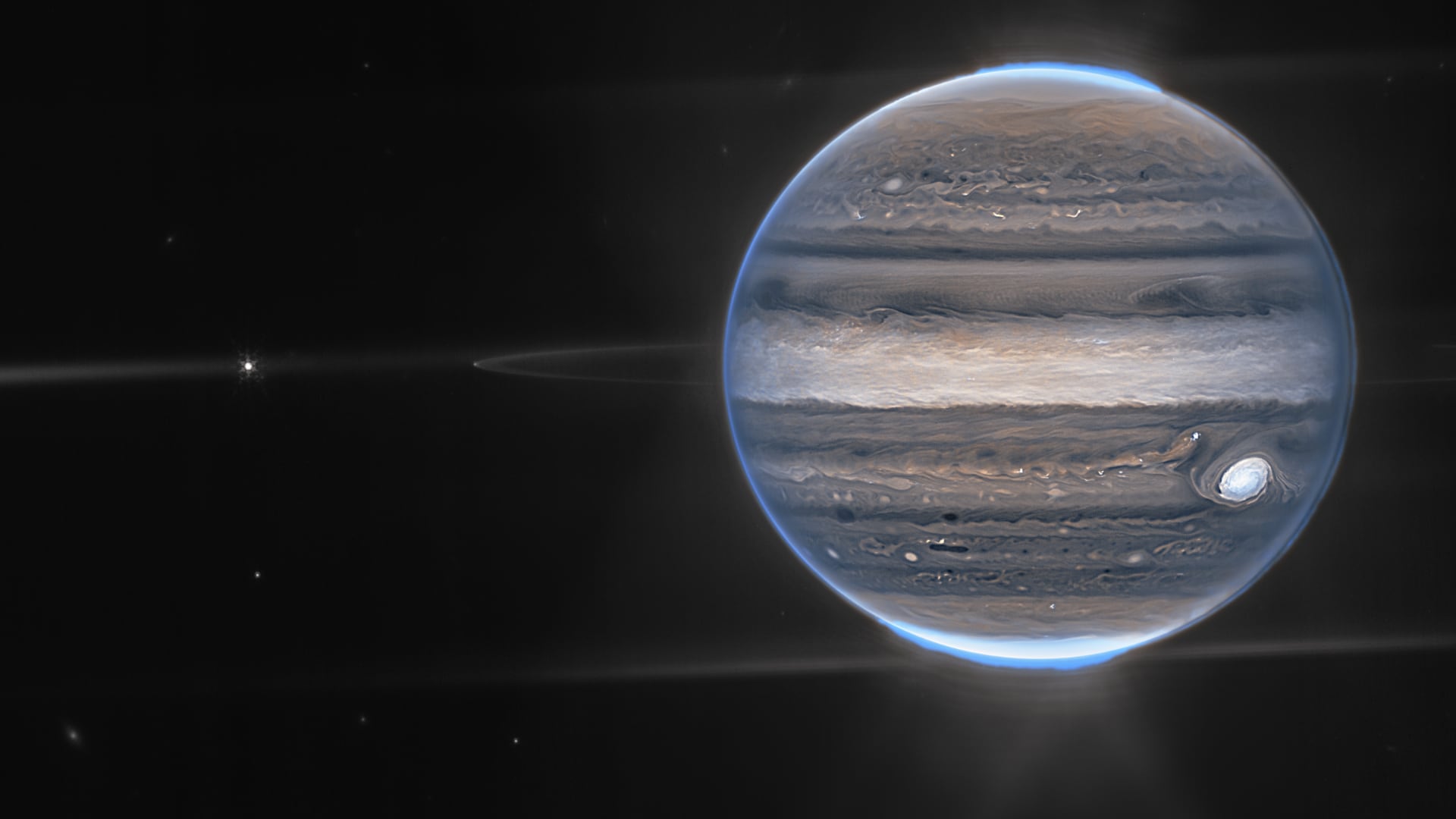

The above rather wonderful image is a composite from the Webb NIRCam taken with three filters – F360M (red), F212N (yellow-green), and F150W2 (cyan) – and some processing alignment due to the planet’s rotation.

“We hadn’t really expected it to be this good, to be honest,” said planetary astronomer Imke de Pater, professor emerita of the University of California, Berkeley. De Pater led the observations of Jupiter with Thierry Fouchet, a professor at the Paris Observatory, as part of an international collaboration for Webb’s Early Release Science program. “It’s really remarkable that we can see details on Jupiter together with its rings, tiny satellites, and even galaxies in one image,” she said.

The images come from the observatory’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and have been mapped onto the visible spectrum (the Great Red Spot appears white in these views, as do other clouds, because they are reflecting a lot of sunlight).

Webb captures the aurora, the gas giant's rings, which are a million times fainter than the planet, and two tiny moons called Amalthea and Adrastea. The fuzzy spots in the lower background are likely galaxies “photobombing” the picture.

While a team at STScI formally processes Webb images for official release, non-professional astronomers — tagged citizen scientists by NASA — often dive into the public data archive to retrieve and process images, too.

Which brings us to Judy Schmidt of Modesto, California, who collaborated with Ricardo Hueso, a co-investigator on these observations, who studies planetary atmospheres at the University of the Basque Country in Spain.

Schmidt has no formal educational background in astronomy. But 10 years ago, an ESA contest, Hubble’s Hidden Treasures, invited the public to find new gems in Hubble data. Out of nearly 3,000 submissions, Schmidt took home third place for an image of a newborn star and has been working on Hubble and other telescope data as a hobby ever since. “Something about it just stuck with me, and I can’t stop,” she said. “I could spend hours and hours every day.”

According to a NASA release on the whole subject, Schmidt says that Jupiter is actually harder to work with than more distant cosmic wonders because of the speed of its rotation, leading to digital adjustments being necessary to stack the images in a way that makes sense.

Webb will deliver observations about every phase of cosmic history, but if Schmidt had to pick one thing to be excited about, it would be more Webb views of star-forming regions. In particular, she is fascinated by young stars that produce powerful jets in small nebula patches called Herbig–Haro objects. “I’m really looking forward to seeing these weird and wonderful baby stars blowing holes into nebulas,” she said.

Likewise…

Comments