Piratez are just disgruntled consumers. In a major new series, Guest Author Gabriel Dusil charts the origins of digital piracy and some of the methods that have been developed to halt its progress.

By Gabriel Dusil

The temptation to steal is almost entirely enabled by convenience. Consumers are only ever a few clicks away from determining who is getting which titles, and when. Some consumers don't have the patience to wait their turn, and simply steal what they want. Impulse buying, when not available, becomes impulse pilfering.

Once upon a time, both prevention and regulation used to be so much easier for content producers and distributors. The simple implementation of varying analogue standards (NTSC4 for North America, PAL5 for Europe6, etc) made sales channel protection relatively simple. This analogue fencing lasted for decades, through the television and VHS7 player age. It even survived the advent of the DVD, even though this was already a digital format. Interestingly, the number of geographical segments increased to six — ostensibly in order to better address purchasing power disparities.

For the most part, analogue encoding was enough to deter cross border selling. Blu-ray discs later carried even tighter encryption, but this did not become a major deterrent for piratez (we will explore the reasons for this later).

The intense competition in the consumer playback market forced manufacturers and brands to differentiate. Multi-region players became a great competitive differentiator and soon became an expected feature effectively nullifying restrictions. Even PC based DVD drives, which had prompted users to ‘choose a region' were soon overcome by hacks, making their forced regionalisation more of a hiccup than true protection.

As computers become popular as a source of entertainment, broadcast standards were no longer an issue, and conversion unnecessary. Computers simply played content natively, in either NTSC or PAL. Leaving content in their original format became the standard approach.

The introduction of HD television in 2005 eliminated many more legacy issues. LCD or plasma televisions began shipping with multiple support for both PAL and NTSC. Furthermore, HD finally did away with some of the dated aspects of broadcast, such as non-square pixels, over-scanning, anamorphic formatting, and finally standardised on a single color gamut (Rec. 709)14. Even interlaced video is now a thing of the past, surmising from the fact that there are no plans for its support in the next H.265 HEVC15 video coding standard.

The computing industry should be thanked for many of these changes. Computers certainly levelled the playing field by allowing support for multiple formats. Content moved from physical discs to files on computers, from physical media to cloud media, from broadcast to the internet. Geo-political borders that prevented playback of entertainment were erased by computers as well as the expansion of the internet. High definition video helped to harmonize the technical differences that plagued broadcasting standards.

This levelled playing field also created an environment wherein computers could be used to break encryption codes established by the entertainment industry. Software could burn discs onto hard drives, and use the internet to distribute pristine copies of content to all corners of the globe. As much as the computer and internet generation helped the broadcast industry evolve, it also opened new doors for copyright infringement on a massive scale.

So, How Did We Get Into This Mess?

The advent of the audio cassette and VHS tape brought copyright infringement to the broadcast industry. This became a hot topic once it was evident that consumers had the ability to easily record radio or television programmes. For the average consumer, the interpretation of copyright law was confusing. Into the 90s consumers were uncertain whether backing up CDs or software was legitimate, even though the practice was wide-spread. A general consensus of how copy written materials could be reproduced was established with the introduction of Fair Use. In the USA this law was incorporated into the Copyright Act of 1976. Ten years after the compact disc was introduced, the Audio Home Recording Act established in 1992 that it was legal to make copies of audio recordings for non-commercial personal use. Fair Use and copyright laws vary on a country by country basis, confusing interpretations of fair usage as technology evolves. Consumers generally follow the principle that making a backup copy is justified if they purchased and have possession of the original CD or software.

Unfortunately Fair Use does not apply to DVD or Blu-ray. The legal issue with films is not in copying the content itself, but in the circumventing the disc’s content encryption. The United States Copyright law entitled Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) 22, passed in 1998 — a little over two years after Blu-ray began shipping — deals with this subject. The DMCA ‘criminalizes production and dissemination of technology, devices, or services intended to circumvent measures that control access to copyrighted works’.

CDs didn't have these measures in place, because music discs are not encrypted. CDs had no copy protection mechanism while at the same time offering pristine audio quality. With the creation of MP3, and subsequent publishing of the standard by the Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG) in 1993, consumers had the means to store their music collections onto their personal computers, or any storage media such as flash discs. Sales of blank CDs soared throughout the 90s, and in 1997 the MP3 player was born26. As flash memory prices decreased, it was possible to carry an entire collection of music in an MP3 player. The appeal of digital theft became overwhelming, and the music industry was caught off guard.

Digitization gave users the ability to make pristine copies of just about anything: Music, Movies, Games, and images. The great limitation of analogue's consistent reduction in quality when copying-from-copies, became moot. Today's digital copies rival that of the original master recordings.

The entertainment industry seemed to have learned from the mistakes of the audio industry when they released the DVD. Not to repeat the copy infringement disaster of the music industry, the movie industry launched the DVD in 1995 using an encrypted format called Content Scrambling System (CSS). This copy protection mechanism failed four years later when Xing Technologies neglected to encrypt the CSS decryption code in one of their DVD players. This allowed Jon Lech Johansen and two unnamed hackers to reverse engineer CSS, and create DeCSS. Several programmes eventually became available which decrypted commercially available DVDs.

The battle against copy infringement continued with Blu-ray. This platform employed the Advanced Access Content System (AACS). Despite significant improvements over its predecessors, SlySoft, an Antigua-based software company announced its ability to crack commercially available Blu-rays. It launched a software package called AnyDVD HD on 17th of February 2007. This unprecedented feat happened only seven months after the first Blu-ray discs shipped. AnyDVD HD was the first package removing restrictions from Blu-ray discs, as well as rendering discs region-free.

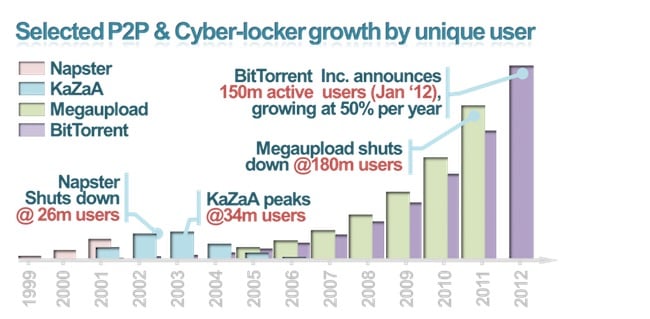

Entertainment in a Borderless Internet

With the global expanse of the internet, it was clear that the age of client-server communications, developed by Xerox in the 70s didn't scale well. A new model emerged in the 90s promoting client-to-client communications, better known as a peer-to-peer34 (P2P) networking. Launched in June 1999, Napster popularised this model, used mainly to facilitate the illegal distribution of music files. It was shut down two years later due to mounting pressure, related to copyright infringement lawsuits. KaZaA emerged a few months later, and added several improvements along the way. This file sharing service peaked at 34 million users in 2003, but began to shrink once the RIAA announced their plans to sue P2P users on 25th of June 2003. Whereas Napster used a centralized structure for indexing and searching, KaZaA implemented a direct user-to-user exchange of information without the need for centralized servers. In other words, when Napster shut its doors, then all subscribers were disconnected from each other. But in KaZaA's case, there was no central source to shut down, making it much more difficult to tear down. KaZaA was later seen to have heralded peer-to-peer's second ‘decentralized' generation.

Just as KaZaA launched, the internet was introduced to the third generation of P2P networking: BitTorrent, developed by programmer Bram Cohen. BitTorrent quickly gained ground as an extremely effective peer-to-peer protocol. The main difference between P2P's second generation and BitTorrent, was how files were located and traded. Services such as KaZaA and Gnutella were user-focused networks — users became part of the network, and sent out direct search requests for files. Responses were then received from other members. Alternatively, BitTorrent takes a file-based approach - everyone interested in sharing a file uses a tracker to essentially create a network dedicated solely to sharing each file.

But peer-to-peer's association with pirated content has resulted in it being synonymous with copyright infringement. Despite this association, P2P has become a viable solution for the legitimate distribution of business and consumer content. Popular subscription services such as Spotify and communications software such as Skype utilize P2P architecture. Possibly one day torrents will be perceived in a more positive light, but for the time being P2P and BitTorrent are tainted by association.

To combat piracy, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) and Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) began an initiative in November 2004 to sue individuals for illegally distributing music and films. By June 2006, over 20,000 people in the United States had lawsuits brought against them.The initiative eventually stopped in 2008 in favour of cooperative enforcement with Internet Service Providers. The most recent iteration of this entails a six-strike policy expected to be enforced sometime in 2013. It involves mounting notifications (strikes) by ISPs resulting in throttling the subscriber's internet speed, and threatening other penalties.

As the internet became a more viable platform to deliver entertainment, the only way that content owners would allow their assets to be distributed, is if secure Digital Rights Management (DRM) solutions existed. Apple was one of the first to popularise the online distribution of music when it unveiled the iTunes Store in April 2003. FairPlay DRM was used to allay the music industry's fears of copy infringement. Apple managed to convince content rights owners - namely EMI, Sony, Universal and Warner - to release their libraries to Apple. In an interesting turn of events, Steve Jobs published an open letter entitled Thoughts on Music in February 2007. The letter encouraged music publishers to remove DRM from their content. Two years later Apple removed DRM from their music library, but maintained protection for video.

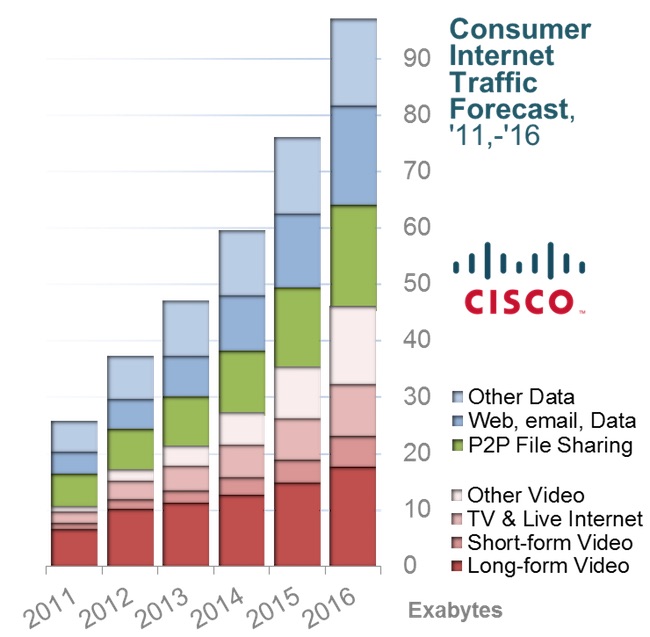

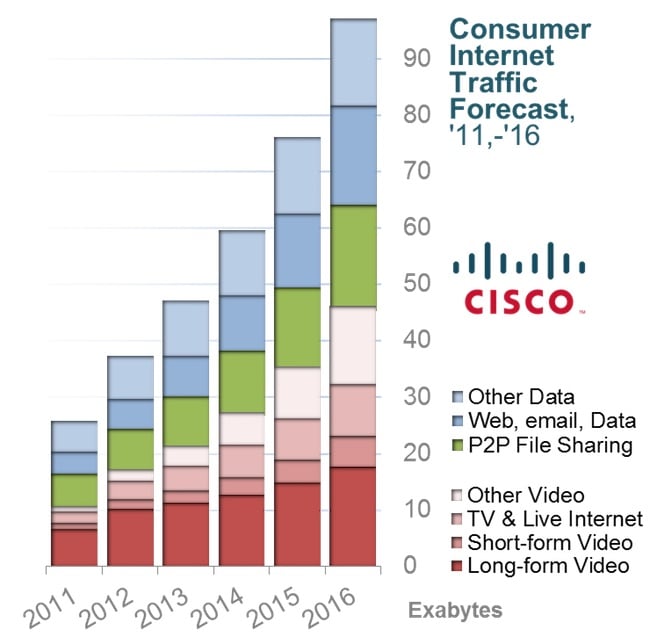

Figure i - Internet Consumer Traffic Forecast '11-'16

Since the turn of the century, album sales have suffered a steady decline, both in unit sales and revenue. The hope was that online distribution would reverse this decline. But even though sales of singles have soared, it has not been enough to compensate for the lost revenue from the sale of complete albums.

The same month that Steve Job published his open letter to the big four music companies, Microsoft entered the online content protection space with PlayReady DRM. This platform protects content when videos are streamed over the internet, and can be used on various portable devices. (Coincidentally this was the same month that SlySoft announced their aforementioned AnyDVD HD hacking software.)

Both Apple and Microsoft have been successful in their in the development of DRM solutions, but consumer pressure has been mounting requiring the need for cross-platform portability. A new standard and protocol named UltraViolet may come to the rescue. UltraViolet lets consumers purchase a DVD or Blu-ray movie, either physically or digitally, and allows them to watch a digital version of the title on selected portable devices. This is achieved through the use of a ‘digital locker’ that stores user rights and allows movies to be viewed onto many different screens without having to repurchase the same title multiple times. The main benefit of this solution is its cross device portability of content and its lack of reliance on a single corporation. UltraViolet is backed by over 70 industry players.

Internet piracy has maintained a steady growth curve over the past decade. Figure ii above shows that piracy continues to rise, with 150 million active users of BitTorrent networks as of January 2012 according to BitTorrent Inc. The storage and streaming service Megaupload based out of Hong Kong had 180 million registered users before shutting down in January 2012. Preventative measures have not appeared to deter the growth of piracy on an international scale. On one hand, it has been argued that the proliferation of piracy enhances the global promotion of content. The borderless nature of the internet certainly enables a wider propagation of content, for better or worse.

So, what is the role of social media in piracy and the entertainment industry? Although still in its infancy, companies such as Trendrr track the relationship between social media chatter and TV ratings. Social networks such as Facebook and Twitter have been identified as a valuable resource to gauge consumer behaviour and viewing preferences in real-time. Netflix is even turning to P2P networks to assess social behaviour in consuming entertainment. Kelly Merryman, Vice President of Content Acquisition at Netflix has been quoted, as saying that the popularity on file-sharing platforms determines, in part, what TV-series the company buys. While this is interesting, the entertainment industry won't be thanking internet piracy for its recent successes.

Some proponents of piracy argue that the act of copying is not strictly theft, since the physical act of theft is viewed as the removal of an item from its owner. Their opinion is that piracy is one of copying, and not displacement of the original item. Whichever way you define it, under the umbrella of copyright law, copyright infringement is a criminal offence.

Cisco forecasts that video streaming will take up nearly half of all global internet traffic by 2016. A further 19% will be used for P2P file sharing - 18.9 exabytes of data, or the equivalent of sending an astonishing two billion HD movies over the web. In any protection strategy, content is only as robust as its weakest link. At the moment, the weakest link in the entertainment industry is the circumvention mechanisms available for DVD and Blu-ray. Next generation protection methods such as 4K UHD content will require far superior protection methods to fortify these assets.

In some markets, peer to peer traffic has declined. According to Netflix, ‘BitTorrent traffic in Canada dropped 50% after Netflix started there three years ago’, attributed to the success of OTT (over the top) services. These online services offer consumers a cost effective, extensive, flexible and immediate on-demand entertainment platform. Consumer purchasing behaviour in the presence of an OTT service suggests that if a viable alternative to piracy is available, then they will likely pay for it, and have a little reason to steal content.

In Part II of Turning Piratez into Consumers, we will further explore issues surrounding piracy, in the form of a gap analysis of what consumers want from their entertainment. We will look at Music, Film, TV, and Gaming individually, and gauge the health of these markets in light of rampant piracy.

In Part III of this series, solutions to reducing the epidemic of internet piracy will be explored from the vantage point of a subscriber wish-list.

Tags: Business

Comments