Intel Exi7

Intel Exi7

We review the Intel Broadwell-E line, which offers performance gains at similar price points as the previous generation. But, does it make sense to make the switch?

Intel's high end 'enthusiast' CPU offerings have proven to be a popular choice amongst studios handling audio or video production work in recent years. Offering class leading processor options based around a modified server chipset, they offer numerous benefits taken from the consumer range, whilst also gaining the extra stability offered by the more mature server platform.

A few generations ago, Intel decided to stagger the life cycle of the enthusiast range behind its consumer counterpart and so we now see launch of Broadwell-E, a good 18 months after the first appearance of the Broadwell platform, which itself has already been superseded by Skylake in the midrange segment. The thinking is that the enthusiast class user wants the stability of a more mature platform and, with the target market containing so many professional users, it makes good sense, although it does sometimes leave those same users lagging behind some of the features that are already being taking for granted in the midrange.

This also gives us an interesting perspective on this new range, having already experienced it once before we already have some idea on what to expect from this refresh. Indeed, the original Broadwell processors were an interesting range, in so far that they never really succeeded in getting a foothold in the market the first time around.

Following on from the popular Haswell generation, Broadwell was a refinement stage, rather than an architecture change, that saw the CPU range make the move to a smaller 14nm processor design. This offered a more efficient chip with a total power usage around 30% lower than on the previous models. It also offered Intel's best on-chip graphics support to date, which made the early Broadwell roll-out ideal to be more focused on the mobile solutions segment. Two chips for the desktop segment followed, but early production run delays and the fact that the low power design largely failed to exceed the performance of the previous generation caused them to fail to make much headway in the market. In fact, the production delay was so long that the desktop chips were only in stores for a few months before the more powerful Skylake successor line was released, whilst the computer world's focus switched to the newer higher performance architecture.

So with that already written stone, the anticipation ahead of the Broadwell-E launch may have been a little muted, although now by having had a couple of years to refine the 14nm production process under their belt and users looking for ever more powerful solutions, is it finally now the time for Broadwell to come of age?

Features and capabilities

One of the key benefits of Intel's two part 'tick -tock' hardware lifecycle ensures that each chipset remains in service over a two to three year period and at least two successive chip ranges. This means that, with a simple bios update the current X99 platform, boards can now accept one of the new CPU’s, giving current high-end users a new upgrade path should they wish to increase their available processing power. The X99 platform at this point is around 18 months old and some early adopters out there are sure to be questioning if this new refresh offers a substantial reason to upgrade. Indeed, users moving up to the segment may wish to know if the new chips should be preferred to the already established older models, so those are the questions we’re looking to answer today.

When looking at the key new features with Broadwell-E, the one that stands out is the inclusion of Turbo Mode 3.0. A new initiative from Intel, it is an additional turbo mode that allows for the strongest single core to be accelerated further than normal, helping to add extra performance for programs that are not already optimized to take advantage of multiple core set-ups. The higher core count chips, in the past, have had many comments passed about single core performance with older or optimized code and, whilst it’s an interesting inclusion this time around, it looks unlikely to have any kind of impact on audio and video applications, which tend to be designed from the ground up to leverage the extra cores where they can. What will be of interest, however, is extra raw power on offer here from the extra cores crammed into this generation.

The headline chip this time around is the 10 core 6950X running at 3GHz with a 3.5GHz turbo that takes advantage of the die shrink to give us the most powerful enthusiast class CPU to date. Alongside, it is the eight core replacement for the previous flagship 5960X, receiving a 200MHz bump to 3.2GHz and a 3.7GHz turbo. Lastly, finishing off the range, we have two six core CPU replacements for the older 5930K and 5820K in the shape of the 6850K at 3.6GHz with a 3.8GHz Turbo and the 6800K running at 3.4GHz with a 3.6GHz turbo.

With these last two chips showing similar performance levels, the biggest differentiator between the two six core models, as with the previous generation, is that the 6800K only has 28 PCIe lane connections on the CPU, as opposed to the 40 PCIe lanes offered by the 6850K. PCIe lane connections offer direct access to the CPU for high bandwidth slot in components like graphic cards and high speed solid state storage. Most users building a system for audio work who only require a single graphics adaptor should find that the lower-end 6800K is more than suitable for their needs, although those doing video work that require additional graphics cards may require the extra support of the higher cost 6850K. Given the 6800K CPU costs roughly a third less than the 6850K, this is a worthwhile distinction to make and can certainly be one part where some prospective purchasers can safely make savings.

Another notable change this time is the adoption of 2400MHz memory officially into the Intel specification. High speed DDR4 memory kits started appearing during the weeks leading up to the initial X99 platform launched, as memory manufacturers clambered to release the highest specification overclocking memory they could. A lot of early X99 platform problems could be attributed to memory compatibility not being perfect or the CPU’s memory controller not always responding well to banks full of memory being run outside of the official specification. Anything higher than the listed Intel specification is technically overclocking in the background. We saw a lot of early BIOS updates being released from manufacturers specifically to ensure smooth operation with the wealth of memory options that appeared on the market.

After an initial few months of updates, everything settled down and, whilst the last generation only officially supported 2133MHz memory, 2400MHz and 2600MHz proved popular and solid solutions in general use, so there's no real surprise to see this increase in the supported speed this time around. Whilst higher clocked memory is widely available, in testing with real time based software like your audio sequencer, as long the memory isn’t a bottleneck, you will tend to find that adding faster memory will offer no real benefits to your system performance. For those doing video editing, having faster memory can speed up your video handling and rendering, but in the music system, going for the memory that meets specification and not exceeding it can pay dividends in system stability, as well as saving a bit of money in comparison with the higher performance alternatives.

Versus the previous generation

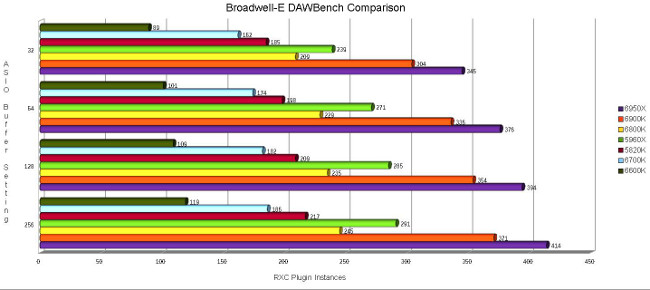

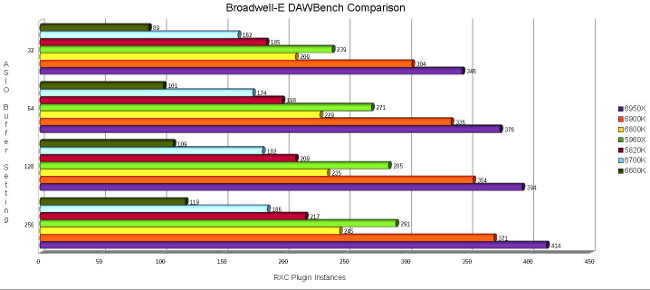

To get an idea on how these new CPU’s line up, we broke out the well-established DAWBench test available from http://www.dawbench.com where you can find a guide for those who wish to learn more. As a quick overview, the test gives us a way to establish a baseline by applying instances of a compressor plug-in over multiple tracks until the audio fails to play cleanly, at which point we’ve established the level where the CPU overhead is maxed out.

I choose to test the 6800K, 6900K and 6950X, alongside the 5960X and 5820K from the last generation, in order to see what gains have been made this time around. I’ve also included the four core i7 6700K, which sits at the top of the midrange currently along with the 6600K which is the most powerful i5 CPU.

Straight away, we can see the contrast between the two ends of the chart with the hyper-threaded 10 core 6950X CPU coming in with almost four times the performance, when compared with the non hyper-threaded four core i5 model. However, with the cost of the 6950X coming in at over six times the price of the i5, it's clear that the chip with the best price-to-performance ratio is to be found elsewhere in the range.

The 5820K and, more recently, the 6700K have vied for that sweet spot with the winner depending on your local pricing. At around the $439/£369 price point, the 6800K makes a strong bid for the crown and, whilst it costs around 15% more than the 5820K at launch, it also offers around 15%-20% more performance in this testing, making it perhaps the best value chip overall in the current line-up.

The eight core 6900K comes in around $1099/£899 with around 50% more performance than the 6800K for roughly two-and-a-half times the cost. It does, however, easily surpass the older 5960X it directly replaces, making it a strong option for those who felt that they may have considered the previous class leader.

The new flagship 6950X takes the range to new performance heights, although also breaks Intel's own pricing records for a non Xeon workstation processor. With a current street pricing of $1750/£1400, the chip on its own is almost the price you would expect to pay for a complete system built around the older 5820K CPU. Whilst its price-to-performance in comparison to the other i7 series is admittedly high, it is well-placed against the current generation of Broadwell EP Xeon chips, with the added bonus of being overclockable in order to gain even more power for your money.

The performance gains found here certainly exceed the ones to be found in the mid-range chips we saw last year, which might be slightly surprising, until we consider that the power draw on these new chips is largely on par with the models they seek to replace. Whereas Intel managed to shave 30% power usage on the midrange Broadwell’s when compared to the previous generation, it makes sense to convert that extra efficiency it had to work with in this design into raw performance for the enthusiast market.

The verdict

What we have here is a nice incremental improvement that offers anyone looking to pick up a new system some extra performance gains for their outlay. However, there is unlikely to be much here to interest most owners of one of the past few generations of performance CPUs, as the gains to be made for the potential outlay may simply prove not to be worth it. Some power users who are already pushing their set-ups, however, may find the new performance levels offered by the 6900K and 6950X tempting, possibly even making them ideal solutions for many professionals, as they do offer new levels of performance for those users who currently find themselves in need of it.

Looking into the future, the release of the replacement Skylake X chipset is pencilled in for around the middle of 2017, meaning that Broadwell-E looks to offer the best value high performance options available throughout the rest of 2016 without stepping up to a dual Xeon based workstation. Overall, it's a welcome upgrade to the range and one that is guaranteed to find a home in many studios over the coming months.

Tags: Audio

Comments