Tiffen DFX 4 Review

Tiffen DFX 4 Review

RedShark Technical Editor, Phil Rhodes, reviews Tiffen's new standalone and plug-in package of digital filters that mimics its popular line of optical filters.

Many companies produce software for filtering both still and moving images, but few have the pedigree of Tiffen. Founded in 1938, the company remains most famous for its optical filters. However, it's becoming equally traditional for organisations operating in fields such as this to dip a toe in the digital waters. The question is how Tiffen's DFX filtering software, which is to some extent a restatement of its optical range, complements the existing product range and how it builds on such a widely-respected history.

The term "restatement" is carefully chosen, because while DFX does simulate some of Tiffen's most famous ranges, including Promist, Soft/FX, and others, it has many other capabilities. Some of the things that DFX does (the Water Droplets effect, for instance), as well as things like bleach bypass and three-strip Technicolor simulations, are not really achievable in optical filtration:

Conversely, there are things like polarisation and highlight-preserving ND that can't really be done in software, so it's quite sensible that DFX is not only an attempt to produce simulations of the real glass, it's also a general-purpose filter set. All this is potentially of use to motion graphics people, as well as photographers and people working in postproduction. With the fourth revision of DFX, there are OpenFX plugins as well as those for Final Cut and Adobe applications, plus a standalone version, so the software is available to effectively everyone.

First take

Initial impressions are quite good. The way some of the filters work does reveal some laudably analogue thinking. The "blacks" slider in the Develop filter, for instance, deepens shadows as one might expect, but without the sometimes-unpleasant side effects of oversaturation you'd risk by trying the same trick with a straightforward levels filter. This is the sort of result one might achieve by extending development time when making a colour print, just as advertised. As with many mathematical filters, this is strictly speaking something that could be done with the inbuilt tools in something like Photoshop or After Effects, but at a quite considerable penalty of time in both the work required to set it up and to render the result. The Develop filter, for instance, seems to implement luminance-dependent saturation control in a way that would require three layers in an After Effects composition to match just that one behaviour.

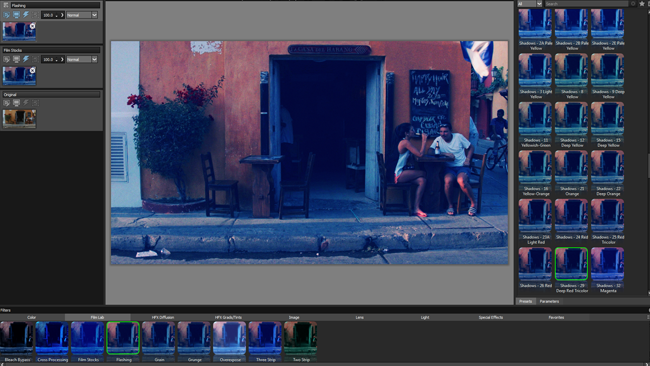

Thankfully, the full DFX user interface (accessible via the plugin controls in most environments) is free from clutter:

Masking and matting controls are presumably included to maintain a consistent interface across the range of plugin types, although in in Photoshop, AE or Resolve (via OpenFX), most users would choose to use the software's native tools.

Simulating optical filtration

Many people, though, will be most interested in the simulations of real filters. Matching live-action footage with a visual effects shot would be a common use case, given that greenscreen material would not usually be shot with, for instance, a diffusion filter. Tiffen also offers an edition of the software for tablets and phones, which seems intended more as a means of auditioning filters in the field.

It's worth bearing in mind that, like any software, DFX will produce the best results when fed well-exposed images without excessive clipping or crushing. There are limits on the precision with which a glass filter can be mathematically simulated. This is true not only of specific optical phenomena, such as polarisation, but also with diffusion and colour filters, especially where the luminance encoding of the input material can only be estimated. The existence of an "input is linear" checkbox on some of the more mathematically-inclined filters (F-Stop and Printer Points among them) suggests that the company is aware of this issue and compensating for it.

While the Tiffen DFX 4 filters do a truly admirable job when presented with properly exposed images, there are certain use cases which require optical filtration. The issue at hand is simply that of dynamic range. The purpose of graduated filters, which are represented in the software, is often to control exposure, frequently of skies. Notoriously, if the sky is clipped going into the software, the best that can happen is for that clipped area to be reduced in brightness, from a featureless white area, perhaps, to a featureless grey area. The reason optical filtration remains popular is that a piece of glass has infinite dynamic range, so that a white light can still punch a clean white highlight through a tinted filter if it's bright enough. Likewise, digital filters like Ultra Contrast can't assist with recovery of shadow detail that isn't there, in the same way that optical Ultra Contrast filters absolutely can improve shadow detail in photographed images.

Dynamic range fix

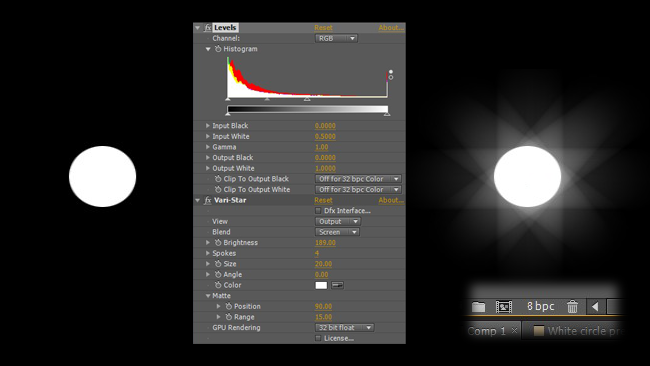

To some extent, the dynamic range problem is solvable, given the right environment. The software supports 32-bit float workflows, meaning that it can handle high dynamic range images, whether those images are of photographic origin or digitally generated. We can demonstrate both the problem with dynamic range and its solution with a simple After Effects composition. First, consider a white circle on a black background, which might represent a shot of a light bulb in a dark room, for example (left). Let's apply the simulated star filter (right).

Now, theoretically, we can use a Levels filter on the white circle before the Star filter, forcing the circle to a higher brightness. This should cause the star to grow in size and intensity. In an eight-bit environment, there's no brighter-than-white value, however, so the result is the same:

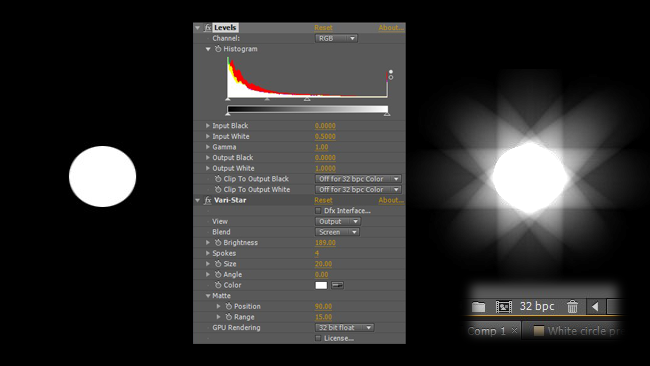

Jumping to a 32-bit float environment, however, allows After Effects to record the brighter-than-white values, and DFX faithfully produces a brighter star.

This should also work on high-dynamic-range images, including log footage stored in higher bit depths, allowing the software to correctly locate (for instance) a flare over the brightest core parts of a sunset. This might work even better still, given the ability to tell DFX that it is operating on log, linear, or other HDR footage, but in the meantime it visually works fine.

The verdict

A few minor concerns aside, Tiffen DFX 4 is a very complete collection and some of the light effects, which exist in a crowded market of flare plugins, are quite novel, particularly the Ice Halos filter, which produces an attractively gentle simulation of parhelia:

Whether the main attraction is the real filter simulation or not depends on the use case, but either way, there's so much to like in Tiffen DFX 4 that it's reasonable to conclude it will offer something valuable to any user.

Tags: Post & VFX

Comments